LYNN EUSAN:

Legacy of a Slain Advocate

In the United States, the year 1968 is often remembered as one of history’s most turbulent.

During the height of the Vietnam War, anti-war sentiment reached a peak and two assassinations jarred the world: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy.

Amid that backdrop, one of the University of Houston’s first African-American students, the co-founder of the African American Studies program at UH, was set to make history.

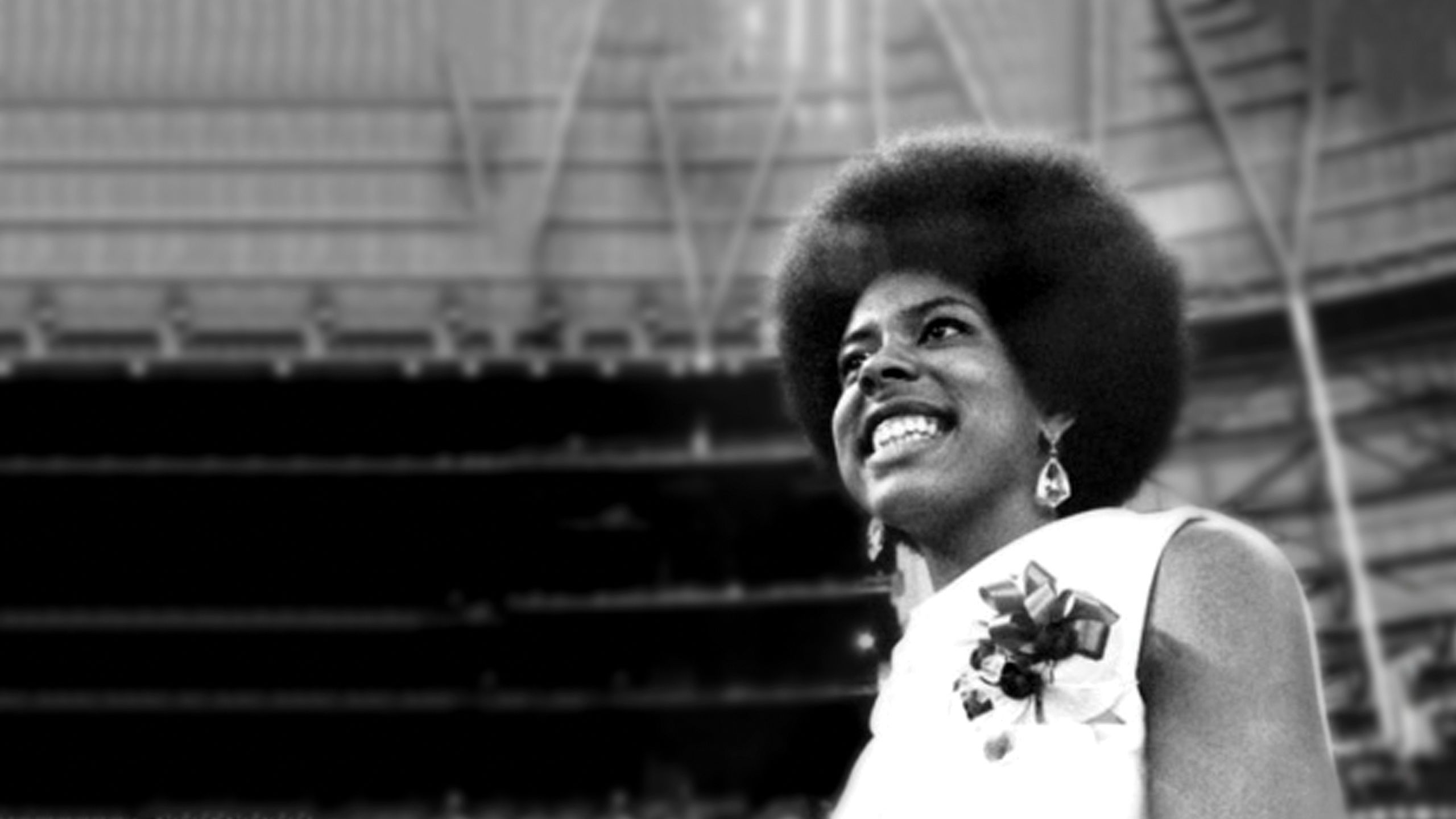

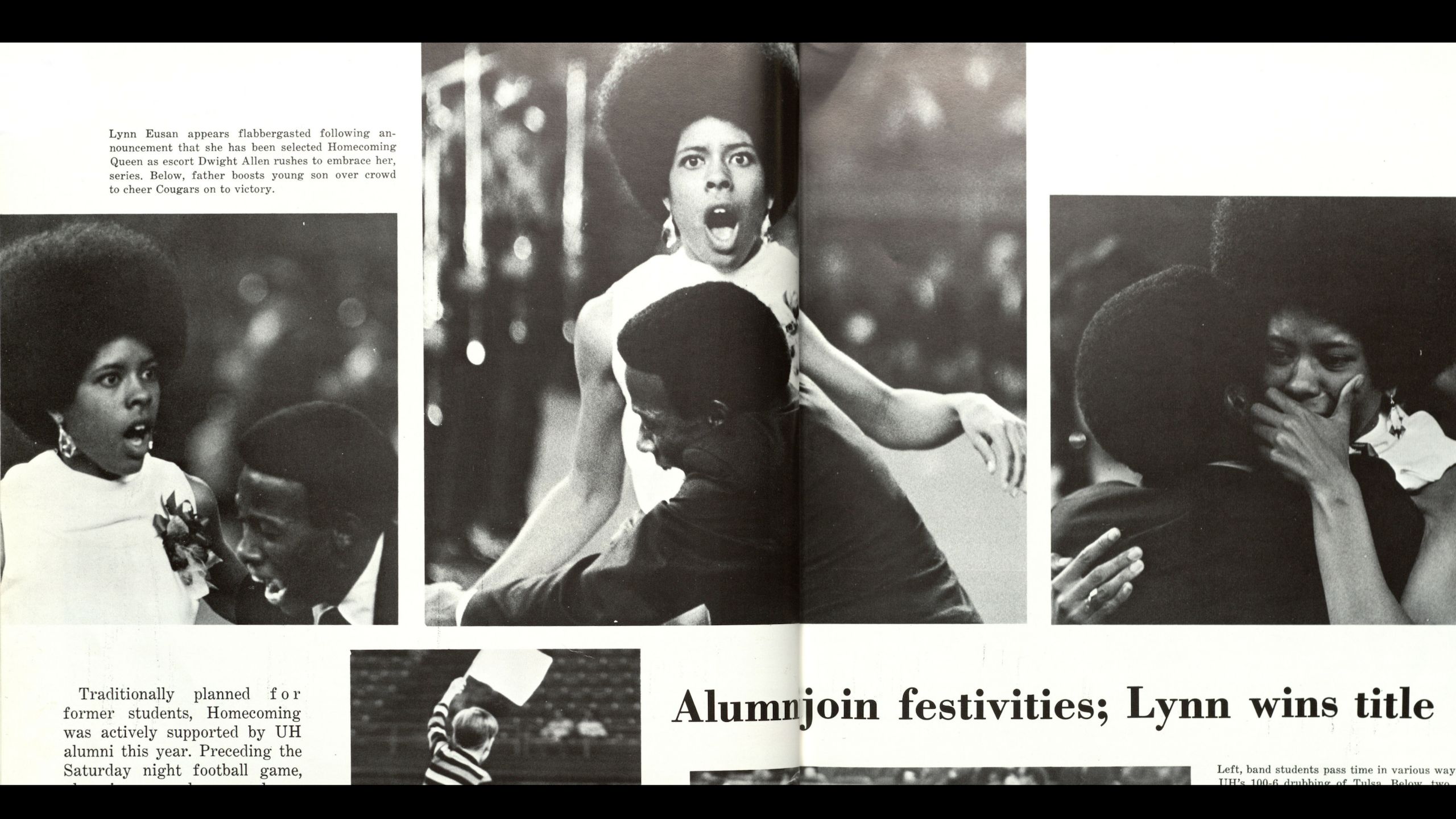

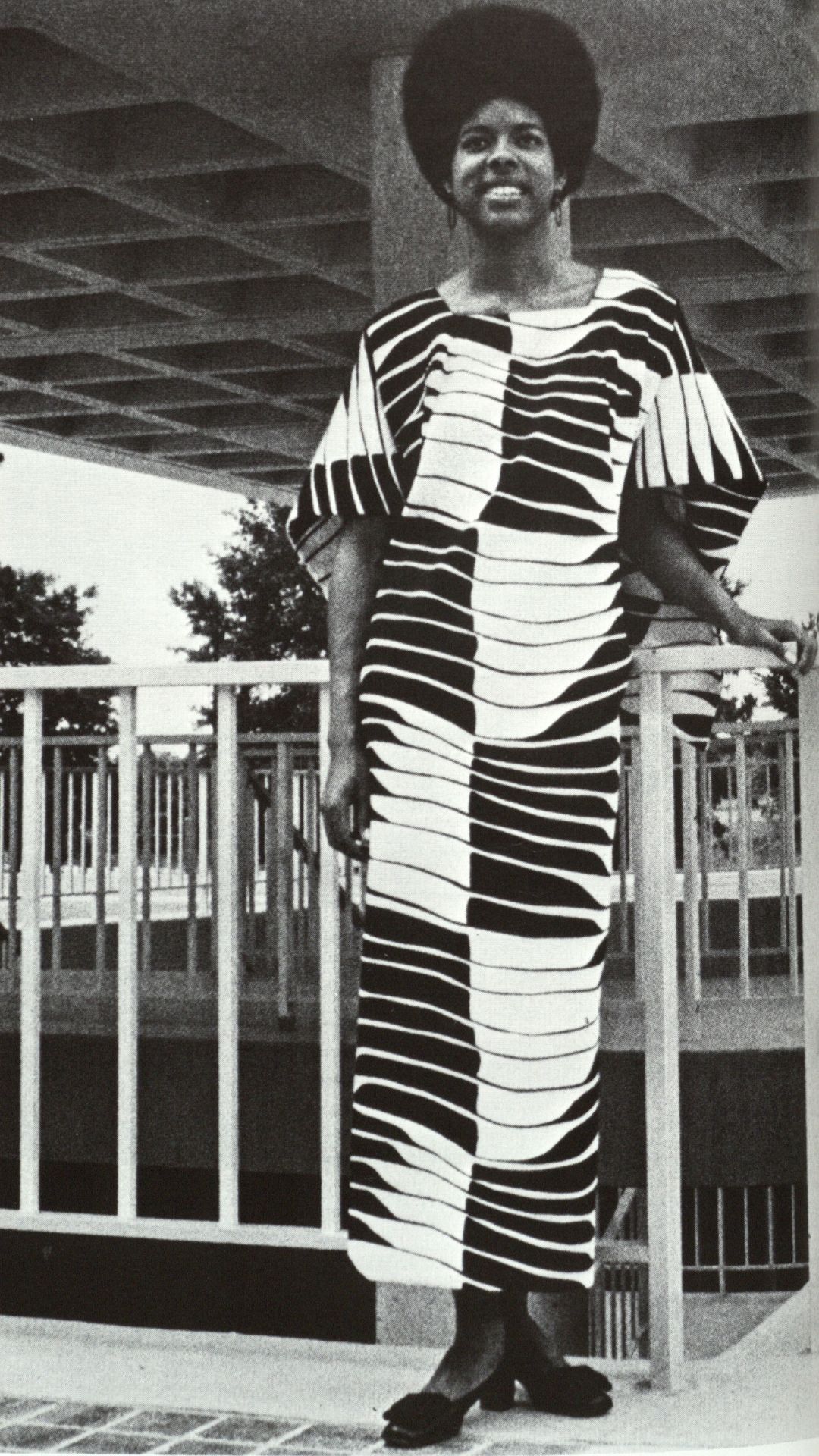

In November 1968, Lynn Eusan was crowned the first African-American homecoming queen at the University of Houston, making her the first at a predominately white university in the South.

No one seemed more shocked than Eusan.

Philip G. Hoffman, UH president from 1961 to 1977

Philip G. Hoffman, UH president from 1961 to 1977

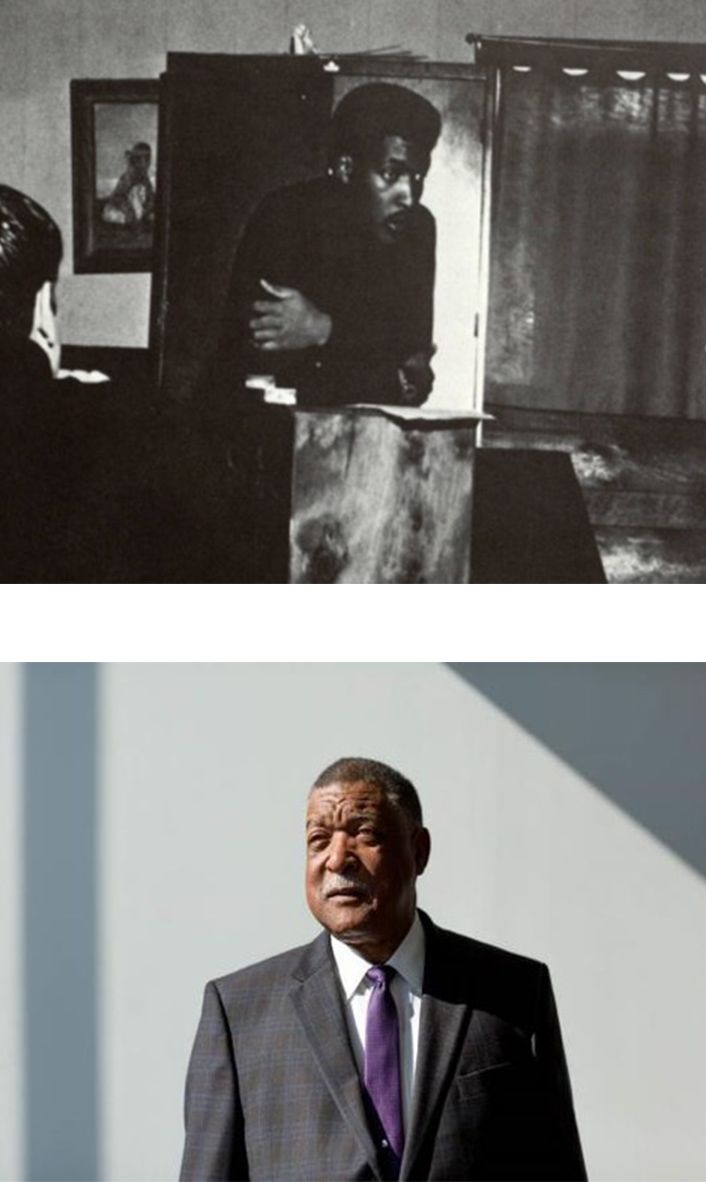

Top: Gene Locke 1968-69. Credit: UH Libraries Special Collections Bottom: Gene Locke 2019.

Top: Gene Locke 1968-69. Credit: UH Libraries Special Collections Bottom: Gene Locke 2019.

“Lynn’s election ... will be a symbol representing UH’s defiance of the wall of prejudice”

“Lynn’s election ... will be a symbol representing UH’s defiance of the wall of prejudice”

Fifty years later, in the fall of 2018, Eusan’s presence would reverberate again on the UH campus when state and federal approval was granted for the University to offer a bachelor of arts in African American studies, the program she helped create. The first degree is expected to be conferred in Spring 2019.

“That’s legacy and impact,” said James Conyers, current director of the African American Studies program. “You have people who come through different historical periods of time and they have an interest in raising different types of questions to have impact, not for popularity, but for equity and once you start raising those questions about disparity you choose a different path.”

And so as time was choosing Eusan, she was choosing her path.

But first, the ‘60s

In the sixties, the majority of UH students—and all the faculty— were white. UH began admitting black students in 1962.

“Integrating was the right thing to do. However, we did not want a Mississippi or Alabama on our hands. We decided to integrate in the summer when there weren’t as many students on campus. We also had a local media blackout for a week so as not to publicize the event,” Philip G. Hoffman, UH president from 1961 to 1977, recounts in the book "Houston Cougars in the 1960s: Death Threats, the Veer Offense, and the Game of the Century."

Six years later, Eusan’s moment had arrived. A black homecoming queen had swept to victory, largely due to efforts of those who banded together and had felt disenfranchised for the school’s first 41 years.

These were “students who no longer wanted to be second or third string and wanted their own cultural identity recognized and respected,” said Gene Locke from East Texas, one of the first African-American students at UH. Locke would become one of Eusan’s dear friends. He would also become an attorney with a storied career including terms as Houston City Attorney and Harris County Commissioner.

He recalls Eusan’s moment, her ascension to homecoming queen, as a convergence of forces. “All of a sudden the African American civil rights movement was full force, followed by a black nationalist movement on the part of African Americans, the plight of women was now front and center and the demand for rights for women, there was a Hispanic movement, then called the Chicano movement, that would not be denied,” Locke said.

"Society was changing and changing rapidly. We can revise history and suggest we had great clarity and knew where we were going. The truth of the matter was, we were 18-, 19-, 20-year-olds who were just out of high school confronting worldly problems." ~Gene Locke

"Society was changing and changing rapidly. We can revise history and suggest we had great clarity and knew where we were going. The truth of the matter was, we were 18-, 19-, 20-year-olds who were just out of high school confronting worldly problems." ~Gene Locke

Locke, Eusan and the handful of black students on campus, were on the frontlines of change on campus in the mid 60’s and they ran her campaign with political furor, sidestepping the role as a mere social distinction. For Eusan, as one of the first civil rights advocates on campus, it was the platform she needed to become a voice for change.

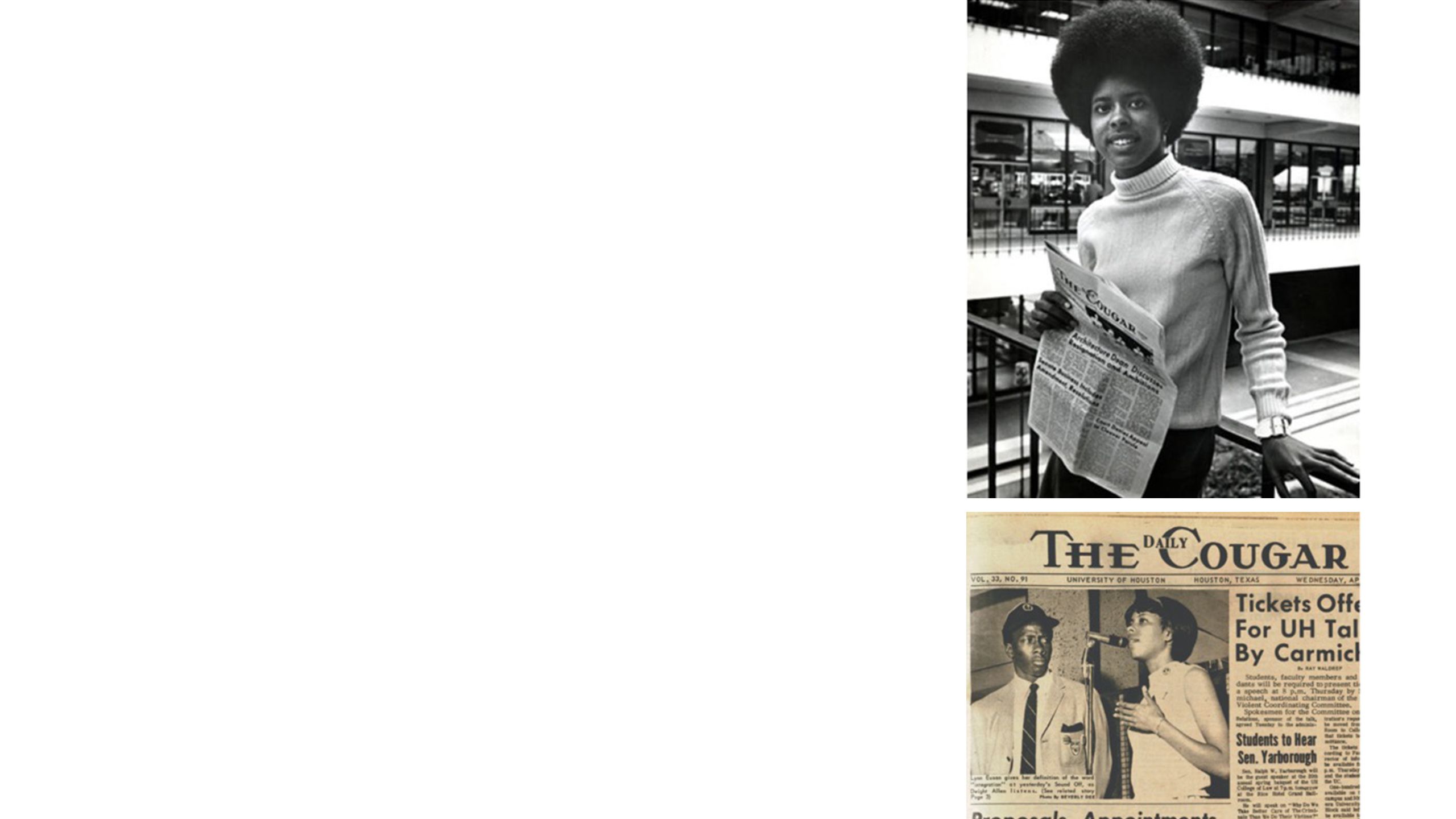

In their endorsement of the candidate, the Daily Cougar summed up, “Lynn’s election to this honored position will be a symbol representing UH’s defiance of the wall of prejudice, and an indication that educated Americans are moving into a new era of enlightenment.”

“We thought of it at the time as ‘How crazy it would be that a black girl could be homecoming queen at the University of Houston?’”

As election night approached, Eusan sensed a victory of a different sort, telling the Houston Chronicle: “This was the first time black students on the campus have banded together and really been effective against overwhelming odds.”

When the big night came, Locke was there, on the floor of the historic Houston Astrodome, as Eusan won the title, beating five white candidates.

“The shock that she was actually named, it was fantastic,” said Locke.

"It belittles Lynn to think of her as a typical homecoming queen and to think of her election as a typical election. Her election was not the traditional 'let's run someone for homecoming queen'... It showed the political fervor at the University of Houston.”

"It belittles Lynn to think of her as a typical homecoming queen and to think of her election as a typical election. Her election was not the traditional 'let's run someone for homecoming queen'... It showed the political fervor at the University of Houston.”

With many interests, Eusan wasn’t to be summed up. She was by turns: Journalist, homecoming queen, activist, advocate, organizer, fundraiser, marching band member and sorority girl.

While she was a charter member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, one of the university’s first black sororities, she was also arrested twice for demonstrating, a common occurrence – maybe even a badge of honor - during the era.

Then came that one title no one asks for, the one that still sends shockwaves:

Murder victim.

In September 1971, just a month shy of Lynn’s 24th birthday, she was murdered. All these years later, the tragedy is no easier to comprehend.

“It was a shock. It still is a shock,” said Locke. “When the word came back we were just in total disbelief, tragic, very sad.”

"The guy who picked her up was not a good guy," said Gene Locke describing the last day of Lynn Eusan's life.

"The guy who picked her up was not a good guy," said Gene Locke describing the last day of Lynn Eusan's life.

A 1970 UH graduate, Lynn Eusan was killed on September 10, 1971. Locke said she accepted a ride to work from a stranger as she was walking in the rain. Her death remains unsolved today.

Police reported that Eusan’s body was found in the back seat of a car driven by Leo Jackson, Jr., who had a lengthy record with 14 prior arrests for rape, assault and armed robbery.

According to Jackson, a hysterical Eusan had assaulted him and stabbed herself and he was trying to drive her to a hospital when he collided with a police car. Eusan’s niece, Andrea Eusan, says her aunt’s death certificate indicates she was stabbed in the back. Jackson was later charged with murder but was acquitted in 1972, shocking many, including Eusan’s family.

A Lasting Legacy

Andrea says Eusan's death left an indelible mark.

But then, so did her life.

“During this period of time it was normative that students were the leadership faces of civil rights, Black Power, Black Arts movements,” said Conyers. “You had a Jim Crowe-segregated adult community and then you had this student community raising questions like ‘Who made this arrangement? Why are we segregated?’”

And one of the clearest voices was Eusan’s.

In 1967 addressing a disconnect felt on campus, Eusan helped fellow students Dwight Allen and Locke organize the multi-racial Committee on Better Race Relations, to promote harmony among UH students.

In Spring 1968, Eusan, as part of Afro-Americans for Black Liberation, which replaced COBRR, presented a list of demands to Hoffman which culminated in a march on the president’s office.

Eusan led a series of “rap sessions” to explain the needs including:

• An African-American studies program

• More black administrators and instructors

• Increase in financial aide

• Raises for maintenance workers

Eusan wanted to bring social justice not just to the UH campus, but to the neighborhoods and institutions surrounding it including the Third Ward and the campus of Texas Southern University.

"There were other blacks here who felt as I did, and who were facing the same problems I was. By organizing into a group, we were able to make our problems known," Eusan told the Houston Chronicle.

And in so doing, Eusan, Locke and their fellow students championing civil rights on campus were instrumental in the new policies and programs that forever changed the face of UH.

“A few very important things that came out of that was increased minority and women faculty members, increase in financial aid and scholarships,” said Locke. “The existence of the African-American Studies program, which is now 50 years old. We demanded that, it was created and it still stands as one of the oldest and most effective programs.”

Lynn Eusan’s legacy also includes the SHAPE (Self Help for African People through Education) Community Center, which she co-founded in 1969. From humble beginnings SHAPE continues as one of the most visible and involved community centers in Houston’s African-American community and has become an organization of international note. Though Eusan would not live to see the broad diversity she helped usher in at the University of Houston, she did see fragments of change beginning. An editorial in the 1969 Cougar yearbook summed up the “active year” this way:

“…in spite of political and philosophical disagreements the feelings for the university unites our campus.

This concern for “our” university is here to stay…and it feels good.”

“It was not just Lynn and I. There were a whole host of students— African-American, Hispanic, white, international students — people who thought: We are here for a certain purpose, it’s time to make a change.”

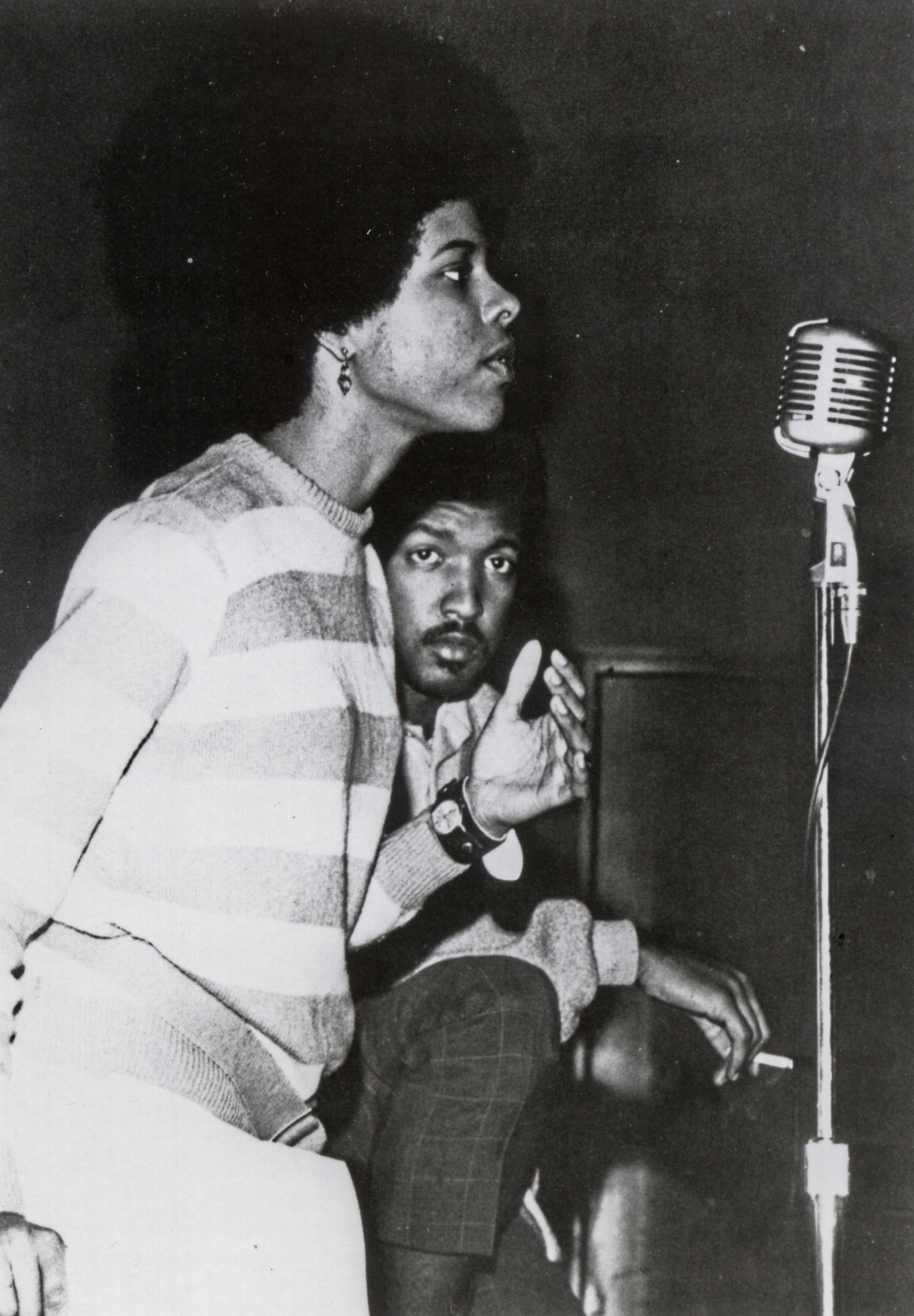

Eusan and Locke at a "rap session" in 1968. Credit: UH Libraries Special Collections

Eusan and Locke at a "rap session" in 1968. Credit: UH Libraries Special Collections

Houstonian yearbook 1969

Houstonian yearbook 1969

Houstonian yearbook 1969.

Houstonian yearbook 1969.

Eusan co-founded the Third Ward's SHAPE Community Center in 1969 while attending UH.

Eusan co-founded the Third Ward's SHAPE Community Center in 1969 while attending UH.

In 1976, the University of Houston (System) Board of Regents named the tree-filled park on campus Lynn Eusan Park. Eusan’s impact lives on in the hopes of those like Locke, who envision future advocates in Eusan’s image.

“I have this hope that somewhere there’s a 10-year old and a 12-year-old who are going to meet up and in ten years they're going to make a difference, and it will be better for my grandkids,” said Locke.

According to The Cougar, Eusan once remarked that she wanted to be remembered for "the cause of justice and equality for all people in this society.”

Conyers said yes, remember her name and say it often. “We need to continue to evoke her name. Not just call out her name but evoke the name to identify individuals who challenged us to be better, that stretched us and they did that because they stretched themselves and challenged themselves.”

For more feature stories from the University of Houston, visit stories.uh.edu.

A communication by the University of Houston Division of University Marketing, Communication and Media Relations.

Do you have a story idea you'd like to share with UH?

Email us at stories@uh.edu. We regret that we cannot respond to every submission. If your submission is a good fit, we will follow up with you directly.