RESEARCH ROUNDUP

From the Labs at UH

Use Your Brain

After conventional rehab stalled, a group of stroke survivors found they continued to gain movement and control after being taught to power an external robotic device with their own thoughts. Harnessing that brainpower is the work of the Non-Invasive Brain Machine Interface Systems Laboratory at UH, led by engineering professor Jose Luis Contreras-Vidal. A clinical trial using the system to help people who have diminished use of at least one arm after a stroke suggests that requiring patients to engage their brains as part of the therapy can take advantage of the brain’s plasticity in allowing patients to relearn movement.

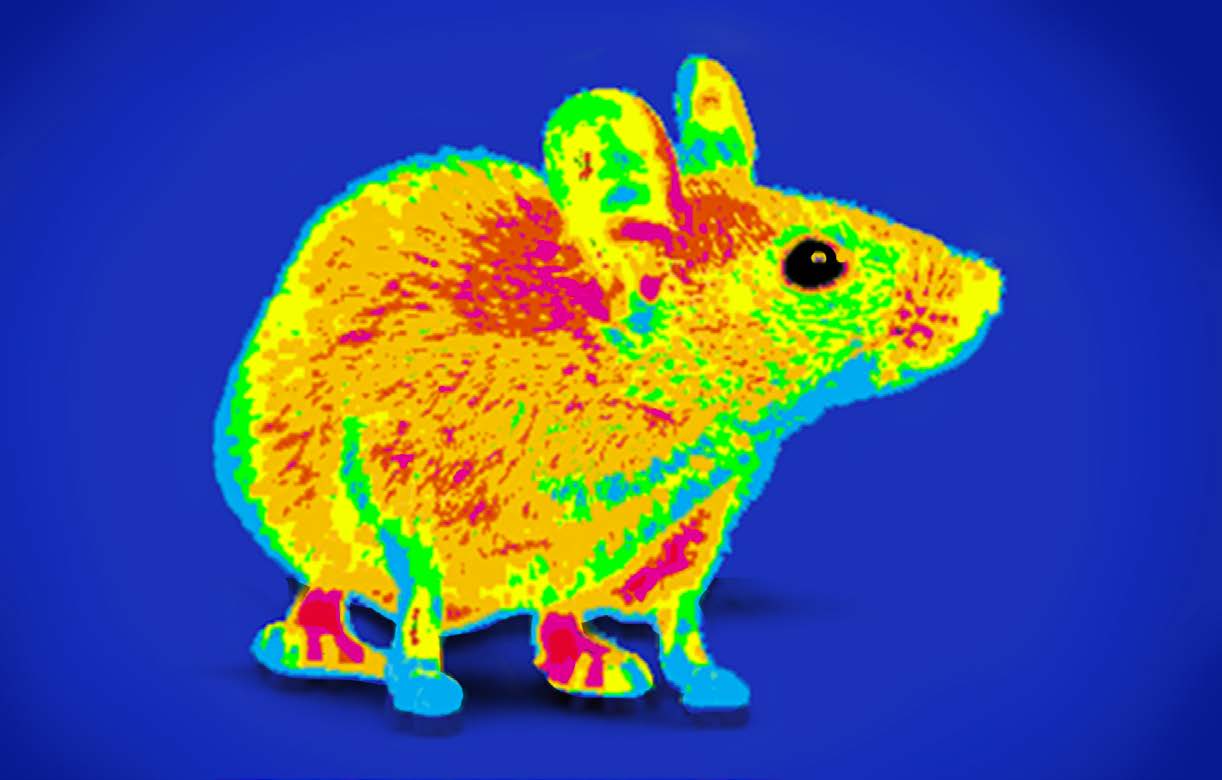

Hot Take

Certain species of snake – think pit vipers, boa constrictors and pythons – can capture prey with uncanny accuracy, even in total darkness. Now we know why. Pradeep Sharma, chair of the UH Department of Mechanical Engineering, led a team that found these creatures “see” in the dark by converting heat into electrical signals. The key? Snakes with a pit organ – a hollow chamber covered by a thin membrane – rely on cells inside that membrane to function as a pyroelectric material, drawing upon the electrical voltage found in most cells and processing the infrared radiation emanating from organisms or objects that are warmer than the surrounding atmosphere to form a thermal image.

Becoming Climate-Friendly, Y’all

Protecting a warming planet is doubly complex in Texas – not only is the state vulnerable to more powerful hurricanes, tornadoes and other extreme weather as a result of climate change, its economy is powered in part by the extraction and processing of the fossil fuels that have contributed to rising temperatures. Researchers from UH Energy and Center for Houston’s Future created a four-pronged path showing how the Houston region can not only survive the coming transition to more climate-friendly fuels but also become a global leader in the movement, with an emphasis on carbon capture, utilization and storage, hydrogen fuels, a sustainable electric grid and better plastics recycling.

Tectonic Mystery Solved?

Geologists long have debated whether a rumored tectonic plate known as Resurrection slid sideways and down into the Earth’s mantle as long as 60 million years ago. Perhaps, some thought, it never really existed. A team of geologists from UH may have changed the minds of those naysayers after reporting that they located the lost plate in northern Canada by using sophisticated tomography images of the Earth’s mantle. That may settle the mystery, but it also could help geologists better understand where to find mineral and hydrocarbon deposits, as well as improve predictions about the risks from volcanoes.

Goodbye to ‘Forever Chemicals’

The synthetic chemicals known as PFAS earned their nickname of “forever chemicals” from their stubborn ability to resist efforts at cleaning up the soil and groundwater where they accumulate. That’s not good – these chemicals pose risks to human health ranging from respiratory problems to cancer. Research led by UH Energy researcher Konstantinos Kostarelos offers a new explanation for why they are so difficult to permanently remove and, perhaps more importantly, offers new avenues for better remediation practices.

No, You’re Wrong

Political polarization has been the subject of endless chatter on cable TV, but a mathematical biologist at UH actually ran the numbers. Alexander Stewart said researchers have created a mathematical model showing a causal link between economic inequality and political polarization. And Stewart suggested the impact can grow. “We also showed that once polarization occurs, it can spread rapidly to the whole population and persist even when the conditions that produced it have reversed.”

Cheaper, Safer, Better

Researchers long have chased the dream of using magnesium as a safer and less expensive alternative to the lithium in the lithium-ion batteries so omnipresent in modern life. But there’s been a problem – previous versions of magnesium batteries couldn’t deliver enough power for practical use. Researchers from UH, led by engineering professor Yan Yao, and from the Toyota Research Institute of North America, have developed a new cathode and electrolyte, which have been the limiting factors for a high-energy magnesium battery and produced one capable of operating at room temperature and delivering a power density comparable to that offered by lithium-ion batteries.

Pandemic by the Numbers

You know the COVID-19 pandemic was bad – and a survey by the Hobby School of Public Affairs has illustrated just how bad, with high levels of infection, job loss and economic pressures, along with soaring levels of stress and anxiety. Two out of three people living in the Greater Houston area reported feeling anxious since the virus began to spread. And that anxiety wasn’t limited to any one group, researchers found. “These negative effects – many of them due to policies designed to slow the spread of the virus – were distributed across gender and racial and ethnic groups,” said the Hobby School’s Pablo M. Pinto. “Few people have escaped suffering from at least some of the painful aspects of the pandemic.”

Take Heart

Pacemakers and other implantable cardiac devices have generally had one of two drawbacks when it comes to monitoring or treating heart problems – they are made with rigid materials that can’t move to accommodate a beating heart, or they are made from soft materials that can collect only a limited amount of information. That could change with the announcement by UH mechanical engineer Cunjiang Yu that he and a team of researchers have created a patch made from fully rubbery electronics that can be placed directly on the heart to simultaneously collect electrophysiological activity, temperature, heartbeat and other indicators. “For people who have heart arrhythmia or a heart attack, you need to quickly identify the problem,” Yu said. “This device can do that.”

A Fresh Look at BPD

Without a clear treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder among adolescents, many clinicians have been loath to make that diagnosis, considering it a mental health “death sentence.” But recent research by UH psychology professor Carla Sharp provides evidence that BPD among younger patients is treatable and they do respond to therapy. “That means we should not shy away from identifying BPD in adolescents and we shouldn’t shy away from treating it,” she said. Sharp, director of UH’s Developmental Psychopathology Lab, explained the anger, depression and anxiety associated with BPD can be addressed with early intervention. “This sends a message to clinicians: ‘Don’t put your head in the sand!’”

Special Effects

While modern chemotherapy drugs are powerful tools in fighting cancer, sometimes the side effects make it virtually impossible for patients to continue treatment. Pharmaceutics professor Ming Hu is turning to an ancient remedy in an effort to change that for at least one chemo drug, Irinotecan, often a last-chance drug for people with late-stage or metastatic cancer. He is leading a team to determine whether the traditional Chinese remedy Xiao-Chai-Hu Tang can protect people taking Irinotecan from a deadly side effect, severe-delayed-onset diarrhea. The longterm goal, he said, is to develop experimental treatments or nutritional supplements that can reduce those side effects, allowing patients to continue with life-saving chemotherapy.

Get Me a Drink

Scientists already have the technical ability to desalinate seawater and create clean drinking water plus energy-efficient hydrogen. But it’s difficult – and expensive. Now, researchers from UH, led by Zhifeng Ren, have developed a new nickel-iron-(oxy)hydroxide catalyst that

will allow low-voltage seawater splitting, simplifying the process and lowering the expense. “We found a way to reduce the cost so commercialization will be easier and more acceptable to customers,” explained Ren, director of the Texas Center for Superconductivity at UH (TcSUH).