STEP BY STEP

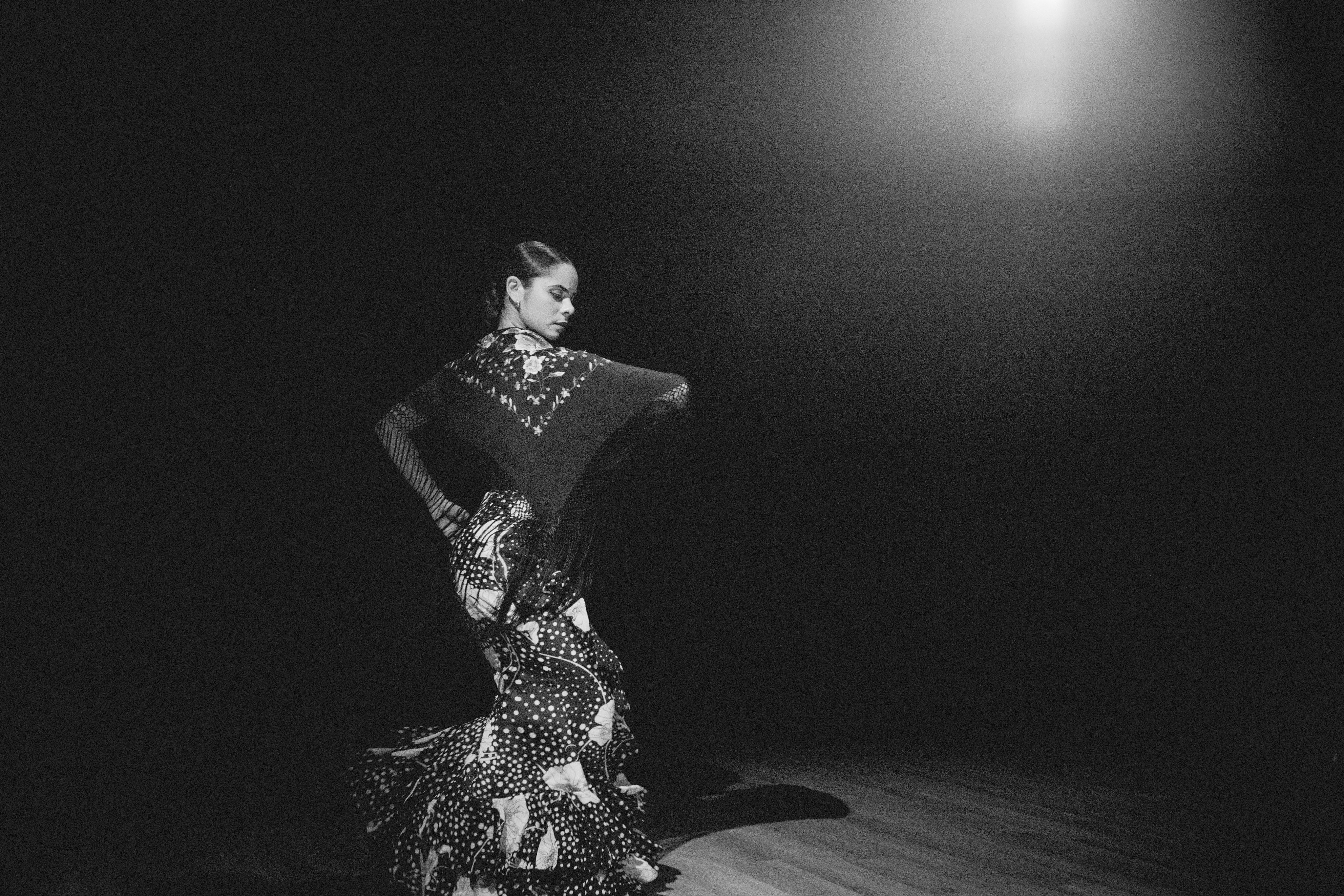

UH flamenco instructor nurtures students’ individuality and fosters a spirit of community by integrating art, history, geography and culture in dance.

By Ginni Beam

Gabriela Estrada was stunned when the University of Houston’s school of dance director invited her to teach flamenco in 2022, a rare opportunity in U.S. higher education. This marked a transformative phase for Estrada and Houston’s arts community.

Estrada’s family loved the arts. “When my mom listens to music, her body transforms,” she explains. “I am that way as well.”

Music, in a way, is Estrada’s first love, and dance is simply a vehicle to embody it. She talks at length about the many benefits of dance — strength, flexibility, dexterity, cognitive development — but they all come back to sheer joy.

Estrada learned ballet and modern dance from dance pioneers in her hometown of Hermosillo, Mexico. After graduat- ing from high school, she had private voice training, performed solo pieces, sang in musical theatre productions, joined a performing group in Mexico City and majored in dance at the University of California, Irvine.

Trained in the art of flamenco in Spain and Mexico, Estrada is passionate about keeping this dynamic, multicultural form of dance alive.

Trained in the art of flamenco in Spain and Mexico, Estrada is passionate about keeping this dynamic, multicultural form of dance alive.

UC Irvine’s Spanish Dance Ensemble was Estrada’s first in- troduction to flamenco dance, and a few weeks after learning the very basics — “this is an arm; this is a foot” — she joined the company, diving headfirst into flamenco’s complex rhythms and subgenres and performing and choreographing local shows. Estrada returned to Mexico after graduating, joined the University of Sonora dance faculty and accomplished her dream of founding a dance college.

When she returned to UC Irvine for her MFA, she was offered the opportunity to teach flamenco and lead the Spanish Dance Ensemble. Once she completed the master’s program, she moved to Seville, Spain — the “heart of flamenco” — to earn her doctorate in Flamenco Interdisciplinary Studies. One of the only people in the cohort who was not a local flamenco professional, Estrada was advised to keep quiet about her studies. After teaching and choreographing flamenco for 15 years, she still felt like a beginner.

“My mindset, now, is to enter a space knowing that people have the basic element of flamenco, which is an attitude and a rhythm, in their breath and in their heartbeat.”

“It was very humbling, but I was determined to learn,” she says. Estrada analyzed the poetic lyrics and octosyllabic verses. She watched professional flamenco artists sweat to perfect their timing. She absorbed documentaries on Spanish history. Her understanding of dance, art, tradition, culture and learning was shifting.

Estrada’s dissertation focused on the contributions of flamenco to ballet, tracing historical exchanges all connected by colonization, travel and artistic collaboration. The first ballet company in the court of King Louis XIV included Spanish folk dancers, whose movements became part of ballet vocabulary. Flamenco was influenced by the African diaspora and various forms of the tango — African, Cuban, flamenco and Argentinian.

“We don’t need to ‘decolonize’ ballet,” she says. “We need to acknowledge its roots.”

Estrada was drawn to UH's diverse community and interdisciplinary approach, which pairs perfectly with flamenco's varied influences.

Estrada was drawn to UH's diverse community and interdisciplinary approach, which pairs perfectly with flamenco's varied influences.

She realized focusing on shape and eye line — elements emphasized in ballet — fundamentally misrepresents flamenco.

“My mindset, now, is to enter a space knowing that people have the basic element of flamenco, which is an attitude and a rhythm, in their breath and in their heartbeat.”

Estrada says she was drawn to UH — a Hispanic-serving tier-one institution — by the leadership of President Renu Khator and Andrew Davis, dean of the Kathrine G. McGovern College of Arts, and their enthusiasm for interdisciplinary instruction.

“Flamenco is a hybrid multicultural art form that integrates a mosaic of historic cultural references from diverse peoples, lands, traditions and artistic expressions,” she says, so the approach “felt like a ring to a finger.” Estrada’s classes incorporate the Spanish language, cultural and geographical references, anecdotes, and discussions about the mutual influence of global cultures in dance development. She recently invited José Galán, director of Flamenco Inclusivo in Seville, to teach her students remotely about adapting the art form for dancers with different bodies and abilities.

“When you think of flamenco, you think of serious footwork,” Estrada says. “You would never think of somebody in a wheelchair doing flamenco, right? It is a mind-shift.” Many of her students will go on to teach their own classes, now prepared to include and empower people long excluded from traditional dance. One of the marks of a transformative teacher, Estrada says, is that they can see the artistry within you and draw it out “like magic.”

Estrada’s classes emphasize the mutual influence of global cultures in flamenco's history and development.

Estrada’s classes emphasize the mutual influence of global cultures in flamenco's history and development.

In addition to teaching, Estrada collaborates as a choreographer for the UH opera and plans to eventually develop a documentary to honor her late mentor, Héctor Zaraspe. She’s thrilled to be reconstructing “Felipe ‘El Loco,’” a lost performance from the 1950s based on the legend of Felix Fernandez. Artists from all parts of Estrada’s life are involved, including her students and fellow faculty at UH and highly regarded Spanish composer Juan Parrilla.

“All this because of the immense support and vision of Dean Davis,” she says.

Things come full circle. Her daughter continues the dance legacy by touring with Ballet Hispanico. Estrada believes in inclusivity and the importance of arts in education.

“The key ‘gatekeeper’ of any learning is the lack of opportunities to learn,” says Estrada. The opposite of gatekeeping is inclusion. “Education matters. The arts matter."

The Heartfelt Expression of Human Emotion

Flamenco comprises three major elements: cante (singing), toque (instruments) and baile (dance). Although dance is what flamenco is generally known for, flamenco began as singing, and singing remains the essence of the art form. The song types (palos) range from profound to lighthearted and determine the complexity of the rhythm and the themes or general mood. Often, these songs convey stories and traditional folklore.

Dancers, in turn, respond with their own emotional interpretation, showing their connection to the music through body and facial expressions. Typically, female dancers incorporate fluid and flirtatious movement and male dancers employ an exaggerated sense of machismo; all flamenco dancing is characterized by intense emotional expression. Movements and steps are diverse and range from stomps and shuffles to flourishes and twirls.

Though instrumentation — primarily guitar playing — was a later addition to the art of flamenco, tocaors (guitar players) are now considered indispensable. Flamenco guitars differ from classical guitars both in their make and in the way they are played. Musicians typically take a cross-legged stance and combine strumming and percussive elements. Less fundamental, but still popular, are instruments like tambourines, castanets and box-shaped cajons. Improvisation is an important part of flamenco toque.

Flamenco was influenced by multiple people groups and cultures, such as the Sephardic Jews and the Moors, but its origin as a genre can be primarily traced back to the Gitano (Roma) of 18th-century Andalusia, Spain. It has been both celebrated as a symbol of Spanish culture and decried as crass and theatrical, stigmatized because of its sensuality and association with marginalized people.

Flamenco experienced a revival in the 1950s and has evolved into a formal art form that UNESCO declared a “masterpiece of the oral and intangible history of humanity” in 2010. While it has certainly been commercialized to attract tourists, many people have dedicated their lives to its art simply out of personal passion.

As time and globalization wield their influence on the art form, the heart of flamenco remains the heartfelt expression of human emotion. Modern flamenco artists and teachers face the exciting challenge of holding onto the essence of the tradition while also rediscovering it for a contemporary audience.