Not long after the war in Afghanistan began in 2001, collegiate wheelchair tennis coach Michael Cottingham received an unlikely offer to bring the power of disability sport directly to the Afghan people.

“‘Do they have tennis courts in Afghanistan?’” he wondered. “Two,” he was told. Despite the obvious challenges, he packed his bags.

For the past two decades, Cottingham has traveled to the far reaches of the world championing wheelchair athletics. Currently an associate professor in the Department of Health and Human Performance at the University of Houston and director of the Adaptive Athletics program, he was instrumental in developing El Salvador’s national wheelchair tennis program in 2003 and is a leading researcher on the quality-of-life benefits of disability sports – independence, self-confidence and increased employment rates are just a few.

On a recent research trip to Dhaka, the densely populated and poverty-stricken capital city of Bangladesh in South Asia, Cottingham learned of a nonprofit social services organization, Sports for Hope and Independence, in desperate need of sport-specific wheelchairs to fill a growing need for its adaptive athletics teams. There are more than a million people living with disabilities in Dhaka, according to estimates by the World Health Organization.

Compared to standard, everyday wheelchairs, the wheels on sport chairs are cambered, or angled outward, while the wheelbase and seat height vary drastically. Sport chairs are also much more expensive, with a starting price of $2,000.

“There are prohibitively outrageous financial barriers to overcome in Dhaka compared to the abundant resources we have here in the United States. Not only does the nonprofit not have enough chairs to fill the need, the chairs they do have are inferior,” said Cottingham, who last year received the Brad Parks Award from the United States Tennis Association in recognition of his outstanding contribution to the sport of wheelchair tennis.

Michael Cottingham, associate professor in the Department of Health and Human Performance and director of the Adaptive Athletics program, is a leading researcher on the quality of life benefits of disability sports.

Michael Cottingham, associate professor in the Department of Health and Human Performance and director of the Adaptive Athletics program, is a leading researcher on the quality of life benefits of disability sports.

“To be able to see into their world has really opened my mind to so many things ...”

-Mathew Yee

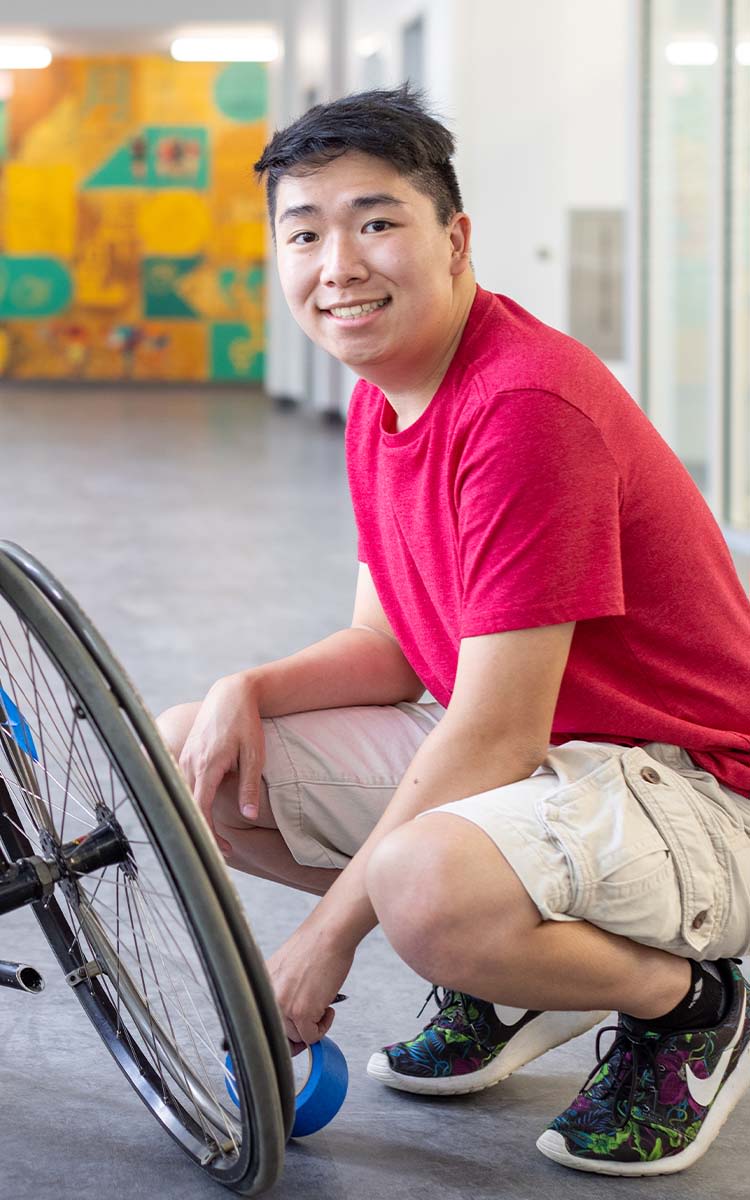

Matthew Yee, a senior majoring in nutrition, is learning about the needs of developing countries as well as deepening his understanding of disability physiology, injury levels and chair seating positions.

Matthew Yee, a senior majoring in nutrition, is learning about the needs of developing countries as well as deepening his understanding of disability physiology, injury levels and chair seating positions.

Matthew Yee, a senior majoring in nutrition, is learning about the needs of developing countries as well as deepening his understanding of disability physiology, injury levels and chair seating positions.

Matthew Yee, a senior majoring in nutrition, is learning about the needs of developing countries as well as deepening his understanding of disability physiology, injury levels and chair seating positions.

ADAPTIVE ATHLETICS CLASS PROJECT

With in-person wheelchair sports paused at UH last spring due to the coronavirus pandemic, Cottingham’s adaptive athletics class shifted focus to the urgent need in Bangladesh. Using his connections across the country, Cottingham secured 40 used sport wheelchairs from generous community-based disability sport programs interested in upcycling their old equipment. Donations came in from New York to Pennsylvania, and North Carolina, Minnesota and beyond.

In need of extensive repairs, the chairs are now being refurbished at UH for class credit by students like Matthew Yee. The class hopes to ship the chairs by boat to the American Embassy in Dhaka, less expensive than sending them directly to Sports for Hope and Independence.

Yee, a senior majoring in nutrition, admits he knew nothing about wheelchairs before enrolling in “Dr. C’s” course. Now he spends class time sifting through piles of miscellaneous nuts, bolts, wheels and axles searching for matches, much like finding the right pieces to a complex puzzle.

“It’s definitely an experience that I’ll take into the future, and I’m very grateful for this opportunity,” he said.

“This is a whole new world for me — working with people with disabilities. To be able to see into their world has really opened my mind to so many things, and I’m happy we can help the people of Dhaka.”

“This experience will help me with empathy for when I become a nurse ...”

-Sherellin Posana

Students are not only learning about the needs of developing countries, but the project includes lessons on disability physiology, injury levels and chair seating positions. Cottingham contests many physical and occupational therapists lack proper training on chair measurement, vital to the effectiveness of the equipment and ultimately the success of an adaptive athlete. He would know. Cottingham is paraplegic — paralyzed from the waist down. He was injured during a hospital accident when he was just a baby but went on to become the first person to ever receive a wheelchair tennis scholarship, and he has competed internationally.

“The University of Houston is such a diverse institution, and the idea that we can provide international service to open doors and access across the world is really a powerful opportunity for students to be involved in,” said Cottingham, who is still working to find a donor to assist with the $18,000 in shipping costs needed to get the chairs to Dhaka.

Senior nursing student Sherellin Posana has interacted with people in wheelchairs through the course of her collegiate studies but never understood the intricacies of chair design and function. Now she can easily identify the grinding sound of a bad bearing.

“I never thought about building wheelchairs and how different they need to be for each person, depending on their injury,” she said.

“This experience will help me with empathy for when I become a nurse, and I will be able to explain to patients how they can benefit from a wheelchair or from adaptive athletics.”

Sherellin Posana, student in the UH College of Nursing, examines the wheel spokes of a wheelchair she is upcycling. It is part of the 40 used sports wheelchairs being prepared for donation to Sports for Hope and Independence in Bangladesh in South Asia.

Sherellin Posana, student in the UH College of Nursing, examines the wheel spokes of a wheelchair she is upcycling. It is part of the 40 used sports wheelchairs being prepared for donation to Sports for Hope and Independence in Bangladesh in South Asia.

Sherellin Posana, student in the UH College of Nursing, examines the wheel spokes of a wheelchair she is upcycling. It is part of the 40 used sports wheelchairs being prepared for donation to Sports for Hope and Independence in Bangladesh in South Asia.

Sherellin Posana, student in the UH College of Nursing, examines the wheel spokes of a wheelchair she is upcycling. It is part of the 40 used sports wheelchairs being prepared for donation to Sports for Hope and Independence in Bangladesh in South Asia.

“Through sports, chair athletes can showcase their ability in society to change people’s attitudes and negative perceptions of disability.”

-Pappu Modak

TRANSCENDING BORDERS

Sports for Hope and Independence was founded in 2016 with a mission to provide sports and recreational activities for the community, focused on child and youth development, girls’ empowerment and life skills development of disabled individuals. Its vision is to use the power of sport to end violence, discrimination and disadvantage by promoting a “sport for all” culture.

Pappu Modak, the organization’s head of sport development, said they’ve been working to expand their adaptive athletics program “for some time now,” but sport chairs are not available in Bangladesh.

“We always find it difficult to train for sport with day chairs in rural communities of Bangladesh. Everyday wheelchairs also limit the ability to perform because of their excessive weight – about 57 pounds – and sometimes players get injured,” he said.

Once Sports for Hope and Independence receives the chairs from Cottingham’s class in Houston, Modak said they will conduct training sessions to educate and advocate for people with disabilities, while also engaging people without disabilities on disability rights. In addition, they will develop a long-term plan to prepare Bangladeshi athletes to compete nationally, and even internationally. There are currently 28 Paralympic sports sanctioned by the International Paralympic Committee.

“Through sports, chair athletes can showcase their ability in society to change people’s attitudes and negative perceptions of disability,” said Modak. “SHI can’t express how grateful we are to Dr. Cottingham and his class for their hard work to support us and to change the landscape of adaptive sport in Bangladesh. We strongly believe that through these chairs, we will be able to serve more people and make a positive change in society by mainstreaming people with disabilities through sport.”

Much more than just a class, Cottingham hopes the Bangladesh project will have an everlasting impact on the adaptive athletes who eventually receive the refurbished wheelchairs and the students who built them.

“Our lab believes that we don’t just do research, we are where research meets application. If we don’t actually change lives and really make an impact, then we’re not doing as much as we should for research,” Cottingham said. “We’re giving our students self-confidence – something to not only put on their résumé, but to put inside their minds and hearts so they know they own it.”

Unable to provide wheelchairs for every participant, SHI organizes inclusive games of sitting volleyball.

Unable to provide wheelchairs for every participant, SHI organizes inclusive games of sitting volleyball.

SHI competitors line up for a race in hospital wheelchairs.

SHI competitors line up for a race in hospital wheelchairs.

Leaning backward in everyday wheelchairs during training sessions often leads to injuries, according to SHI.

Leaning backward in everyday wheelchairs during training sessions often leads to injuries, according to SHI.