Sigmund Freud London Exhibit Co-Curated by University of Houston Scholar

Antiquities Reveal Freud’s Developing Practice

of Exploring the Mind’s Layers

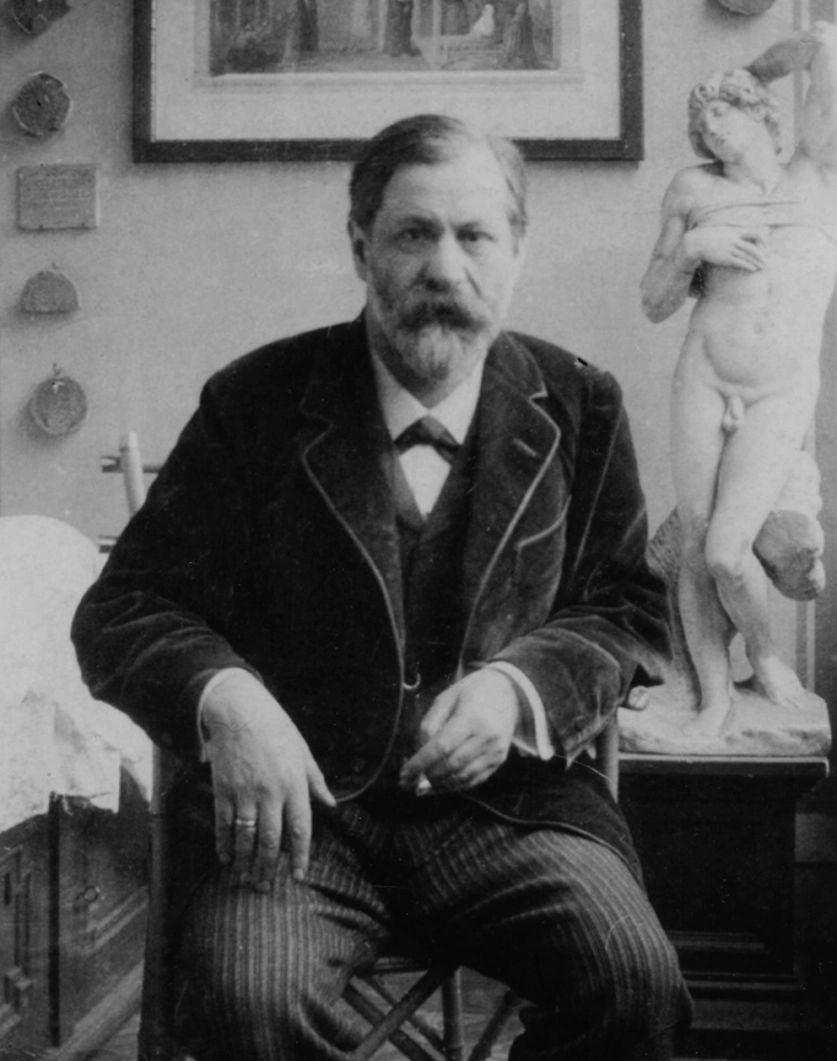

Sigmund Freud next to his copy of Michelangelo’s “The Dying Slave,” in 1911. Photograph courtesy Freud Museum London

Sigmund Freud next to his copy of Michelangelo’s “The Dying Slave,” in 1911. Photograph courtesy Freud Museum London

The father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, did not stop at peeling back the layers of the mind to find the genesis of a patient’s psyche. He did the same with ancient civilizations, collecting over 2,000 historical artifacts and antiquities that revealed layers and flavors of ancient life.

He had Greco-Roman statues, Egyptian mummy bandages, Etruscan vases, Neolithic tools and phallic-shaped amulets from Pompeii. Some of his collection might even open a window into his own multi-layered mind.

Linking Freud’s collection and his theories is the exhibit “Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire” at the Freud London Museum, his former home and office. The collection and accompanying digital archive containing videos, podcasts, photographs and interpretative texts that will live on forever, explores how his collection of ancient objects helped him develop the ideas and techniques of psychoanalysis.

It is co-curated by Tom DeRose and Karolina Heller of the Freud Museum London and by professors Miriam Leonard, University College London, Daniel Orrells, King’s College London and Richard Armstrong at the University of Houston. All three universities funded the exhibit.

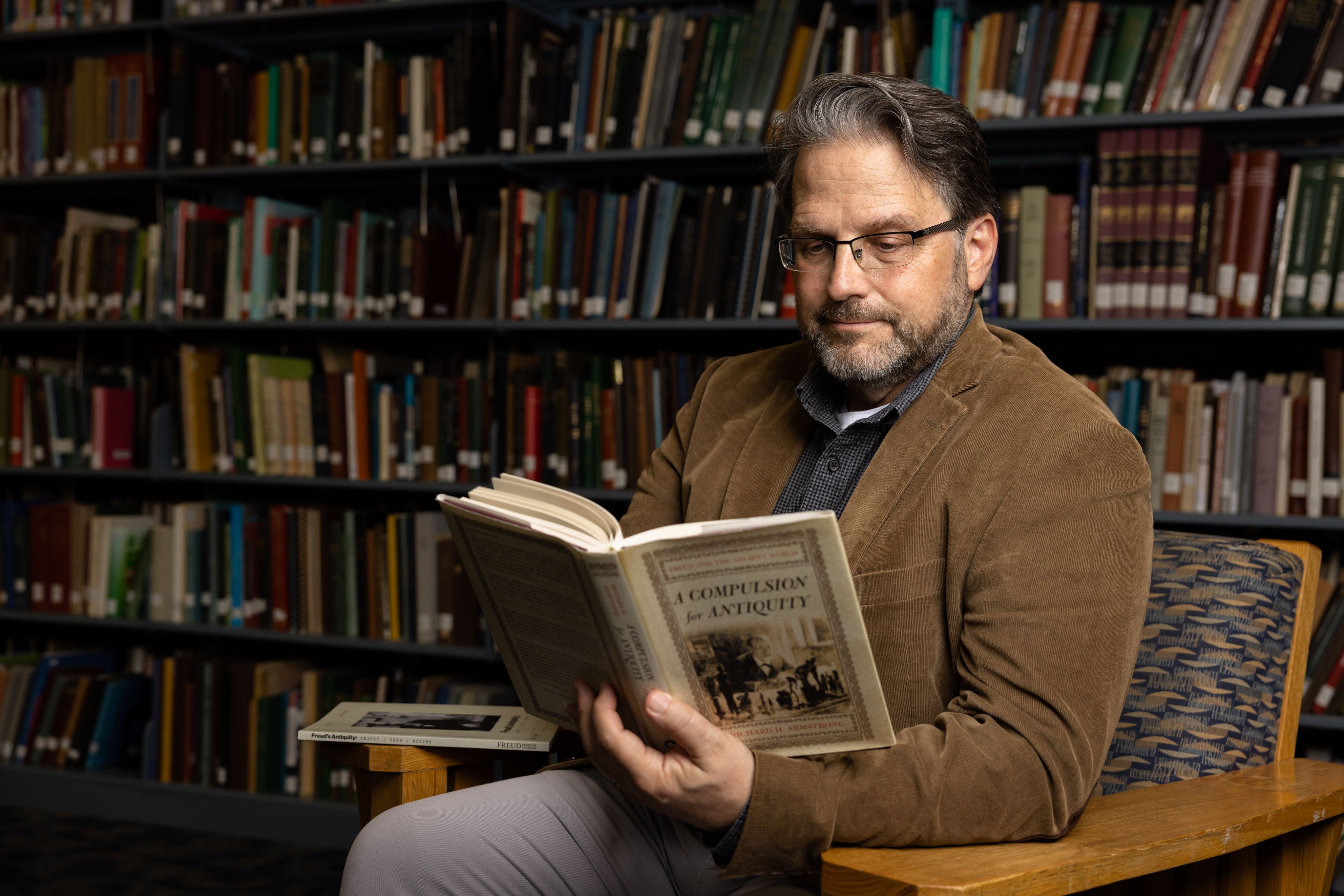

Richard Armstrong, an associate professor of classical studies, is the author of “A Compulsion for Antiquity: Freud and the Ancient World,” and an undisputed expert in the field. He’s currently putting the final touches on his next book on Freud.

Richard Armstrong, an associate

professor of classical studies,

is the author of “A Compulsion

for Antiquity: Freud and the Ancient

World,” and an undisputed expert in

the field. He’s currently putting the

final touches on his next book on Freud.

“Most prominent when you look at this collection is the idea that psychoanalysis is a kind of archeology,” said Armstrong. “Early on, as Freud was developing the methods of excavating the mind through free association, he was engaged in clinical improvisation, making it up as he went along. He had to have a way of explaining to his patients what they were actually doing so they could understand the process, and archeology was an acceptable and exciting profession that helped them relate.”

The exhibit focuses on six separate aspects of Freudian theory alongside representative objects, spanning his entire psychoanalytic career from the early paper “The Aetiology of Hysteria” (1896) to his final completed work “Moses and Monotheism” (1939).

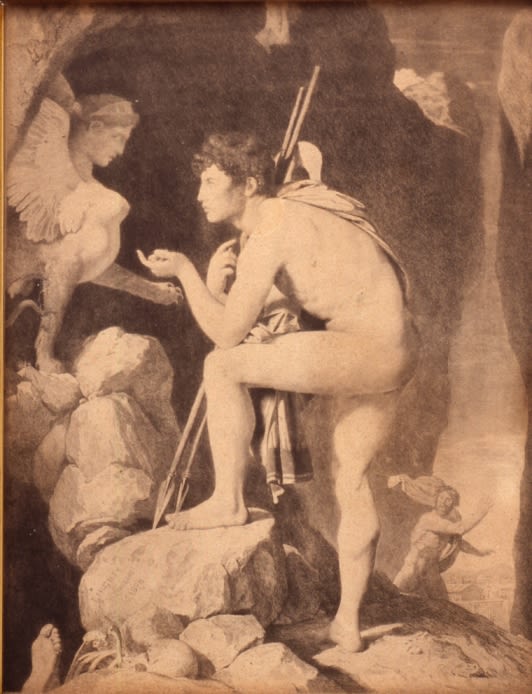

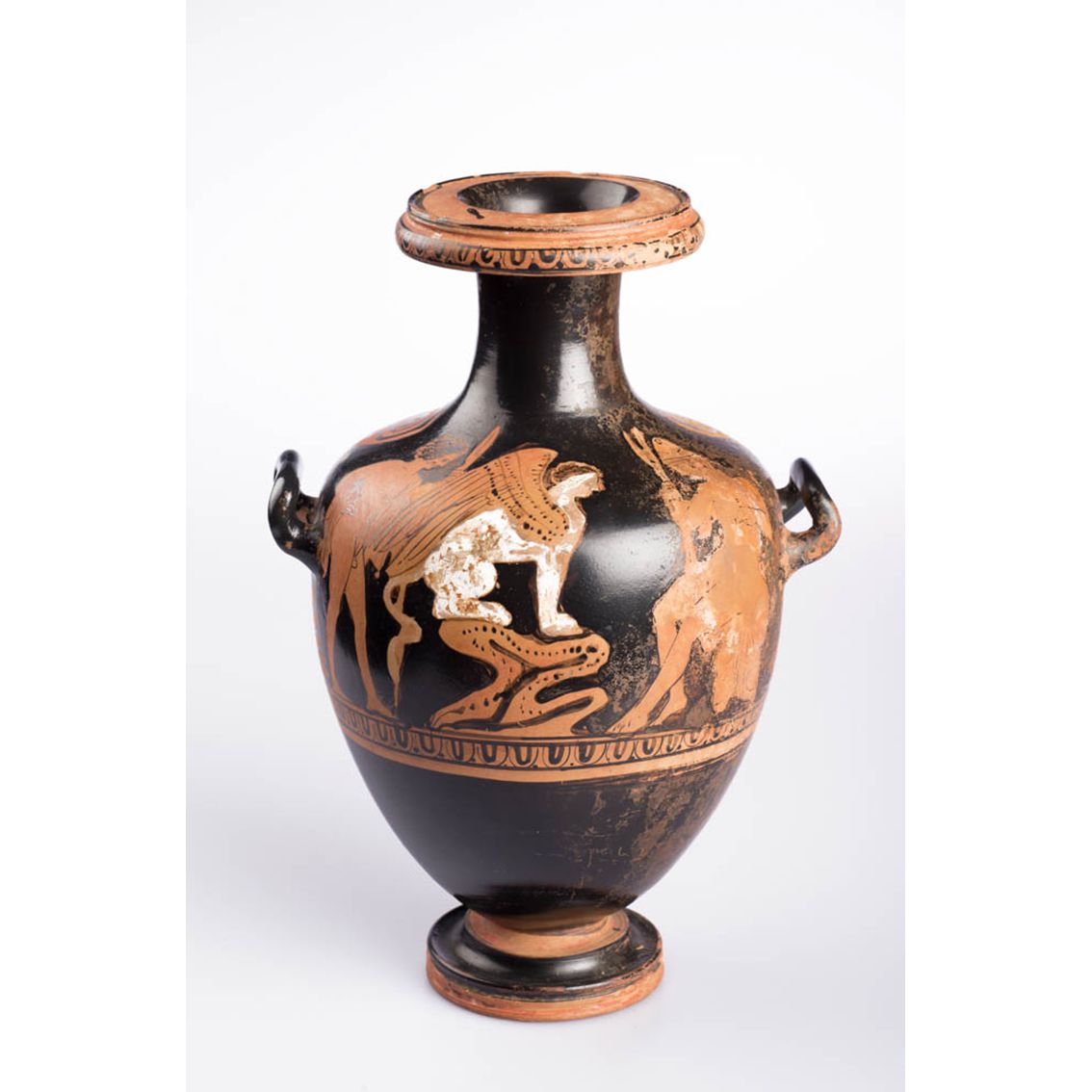

It should come as no surprise that among the artifacts are items connected to Freud’s engagement with Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex.

A vase here, a painting there. And so many other profound works of art.

“Any modern psychotherapist looking at Freud’s consulting room would immediately tell you that no therapist today would work in a room like this. It is too full of objects, they are too suggestive, but he absolutely did. We know from reading accounts from patients that he would hold up objects to describe his excavation of the unconscious,” said Armstrong.

Freud's psychoanalytic couch. Photo courtesy of Freud Museum London

Freud's psychoanalytic couch. Photo courtesy of Freud Museum London

Reproduction print of Oedipus and the Sphinx by Ingres in wood gilt frame. Photo courtesy of Freud Museum London

Reproduction print of Oedipus and the Sphinx by Ingres in wood gilt frame. Photo courtesy of Freud Museum London

“Most prominent when

you look at this collection

is the idea that psychoanalysis

is a kind of archeology."

- Richard Armstrong

Red-figure hydria depicting the myth of Oedipus and the Sphinx from the Apollonia group. Photo courtesy of Freud Museum London

Red-figure hydria depicting the myth of Oedipus and the Sphinx from the Apollonia group. Photo courtesy of Freud Museum London

Bronze Luristan standard finial with a man restraining two lion-like animals, which face outwards. Photo courtesy of Freud Museum London

Bronze Luristan standard finial with a man restraining two lion-like animals, which face outwards. Photo courtesy of Freud Museum London

The journeys – of the objects and through

the mind

How the massive collection landed in London – barely escaping the Nazis’ rampage and persecution of Freud as a Jewish psychoanalyst – may inform some of Freud’s resolve, determination and work. In 1938, as the walls closed in during the Nazi occupation, his works banned and books burned, a Nazi flag draped over his office, the Freud family fled to London, smuggling out the priceless artifacts and even his coveted couch, now proudly displayed in the museum.

“He was very much a refugee, and he waited a long time before leaving Vienna, partly because he may not have fully believed that the kind of anti-Semitic savagery that was going on in Germany would happen in Austria,” said Armstrong. “Of course, he was proved wrong as Hitler himself was Austrian.”

Thus, in the last station of the exhibit “Moses and Monotheism” takes a deep dive into Freud’s relationship with his religion. He describes the Bible in the same way as Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, as a work that contains different layers of meaning.

Separating the layers in the museum was no small feat either.

“If you go to the Freud Museum, and you go on the first floor where there is Freud’s desk, antiquities, all his books and artwork, the first thing you feel is it’s like he just left yesterday. It preserves a sense of his presence because it is such a personal world. And that’s what his daughter, Anna Freud, wanted. It’s been left like that since the day he died,” said Armstrong.

Examining so many items of such historical value can also be overwhelming. So, the exhibit was deliberately staged in a minimalistic way to help visitors focus on particular objects and books that relate to the theme for that station.

“It helps you focus on the relationship between objects and his process of collecting and development of ideas. And that has gone beautifully,” said Armstrong.

As has the publicity on the exhibit. Read the New Yorker article here.

“If you go to the Freud Museum, and you go on the first floor where there is Freud’s desk, antiquities, all his books and artwork, the first thing you feel is it’s like he just left yesterday. It preserves a sense of his presence because it is such a personal world. And that’s what his daughter, Anna Freud, wanted. It’s been left like that since the day he died.”

- Richard Armstrong