UH Addresses Teacher

Shortage Through Innovative Certification Program

$3.5 Million Grant from Houston Endowment Supports Intense Training, Increased Mentoring for New Teachers

UH Addresses Teacher

Shortage Through Innovative Certification Program

$3.5 Million Grant from Houston Endowment Supports Intense Training, Increased Mentoring for New Teachers

Story By Jeannie Kever | Design By Marcus Allen

Districts across the Gulf Coast had to scramble to fill thousands of teaching vacancies this fall, evidence of a critical problem facing Texas schools — fewer certified teachers are entering the profession, even as retirements and resignations have increased the need.

The College of Education at the University of Houston is launching an innovative solution, using a $3.5 million grant from Houston Endowment to create a high-quality alternative certification program that combines key components of the college’s nationally recognized traditional degree program with a shortened timeframe to get aspiring teachers into classrooms more quickly.

A pilot program began this summer, and the effort is ultimately expected to double the number of certified teachers produced by the College of Education.

“This is a way to fast-track the preparation of people who already hold a college degree, to help them become well-prepared to be in the classroom,” said Dean Cathy Horn. “The practical reality is that we have, for the last several years, started the academic year with thousands of classrooms being taught by long-term substitutes, by uncertified teachers or just empty, with students sent elsewhere. That means kids are starting school without the stability of a qualified teacher to set them up for success.”

“Our growing region employs more teachers than some entire states, such as Tennessee, making it critical that we open additional pathways to the profession.”

- Ann B. Stern, president and CEO of Houston Endowment

The teacher shortage is a statewide crisis, but the fast-growing Houston region warrants particular attention as it represents about a quarter of the state’s school-age population, according to the Texas Demographic Center. Strengthening public schools is a priority for Houston Endowment.

“Our growing region employs more teachers than some entire states, such as Tennessee, making it critical that we open additional pathways to the profession, and teachers who are better prepared in a high-quality program are more likely to stay in the classroom,” said Ann B. Stern, president and CEO of Houston Endowment. “We are proud to support this innovative program from UH, which will strengthen the pipeline of well-prepared and supported teachers and help us more quickly meet the demands of the teacher workforce.”

UH’s alternative certification program, or ACP, will distinguish itself with a commitment to high-quality, research-based preparation that involves strong partnerships with school districts. Participants, who must have a bachelor’s degree, will benefit from intensive upfront training taught by college faculty, on-site coaching and support from an experienced mentor, and professional development sessions throughout their first year in the classroom.

“This generous grant from Houston Endowment is instrumental in helping the University of Houston address one of our region’s greatest workforce challenges, meeting the need for more highly trained teachers,” said Diane Chase, senior vice president for academic affairs and provost.

Jeremy Sapp, assistant director of leadership development in the Fort Bend Independent School District, said the district was pleased to partner with UH on the pilot alternative certification program and praised the focus on increased support for the new teachers.

“We thought it was a way to get quality teacher candidates,” Sapp said. “We knew UH runs a quality program and produces quality teachers.”

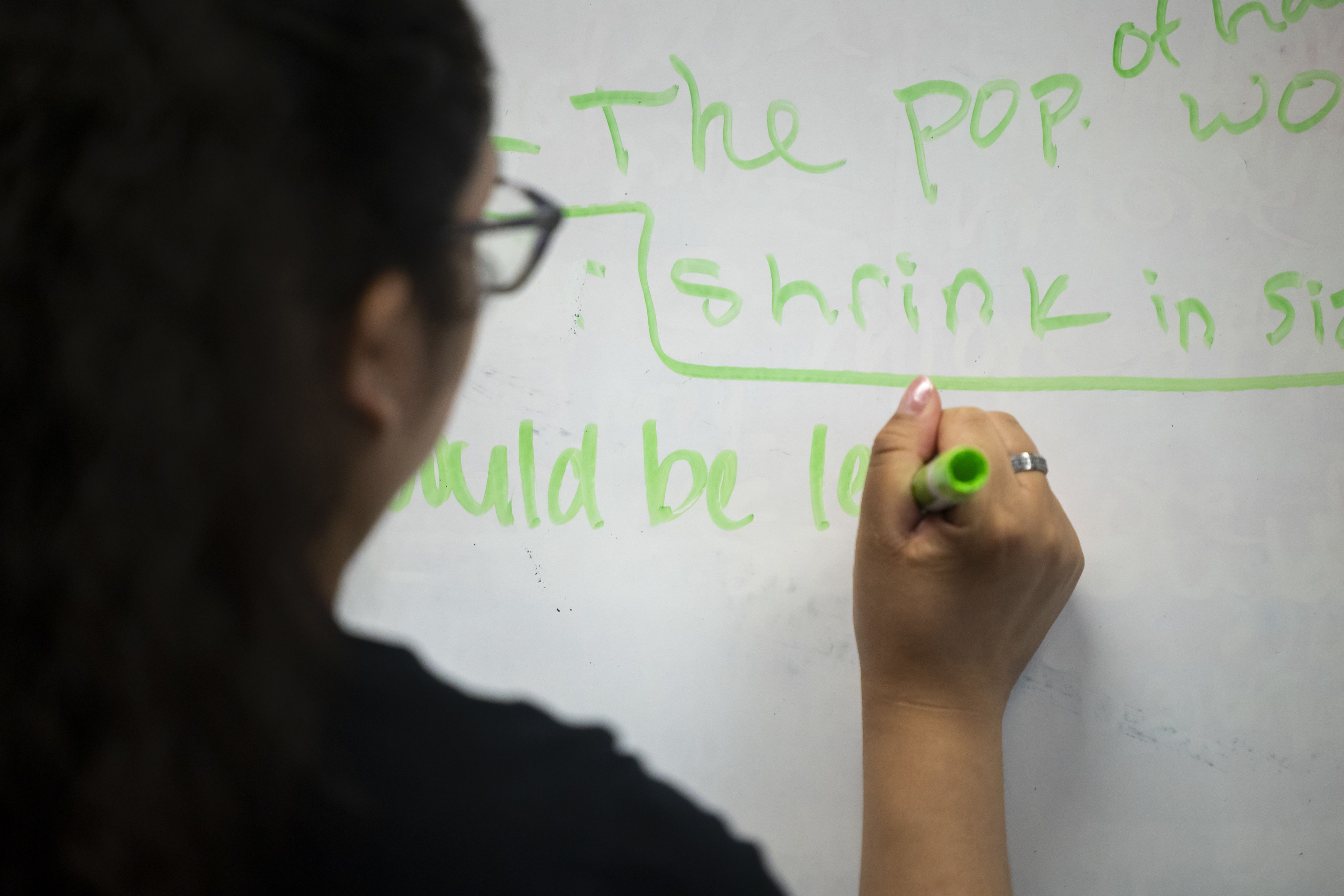

Casie Ellison said the intensive training she received over the summer as part of the pilot program gave her confidence before she began teaching kindergarten in Fort Bend ISD. “It’s been very helpful,” she said. “We had good teachers who have modeled different teaching strategies, and we had opportunities to practice them ourselves.”

Participants spent three weeks on the UH campus before beginning work as the teacher of record —earning a first-year teacher’s salary — in the initial participating districts, Fort Bend ISD and Aldine ISD. Throughout their first year, the group will meet both in person and online to build their teaching skills. A site coordinator will provide formal and informal coaching through frequent classroom visits and meetings. Participants can pursue state certification after their first year on the job.

Amber Thompson, associate chair of the UH teacher education program, and Shea Culpepper, director of the program, said the goal is to translate the tenets of strong teacher preparation to the faster timeline of the alternative certification program.

“We know we need multiple pathways into certification to meet the need for teachers,” Thompson said. “And we’re committed to delivering best-in-class preparation so teacher candidates are classroom ready to help all students succeed.”

Creating Classroom Leaders

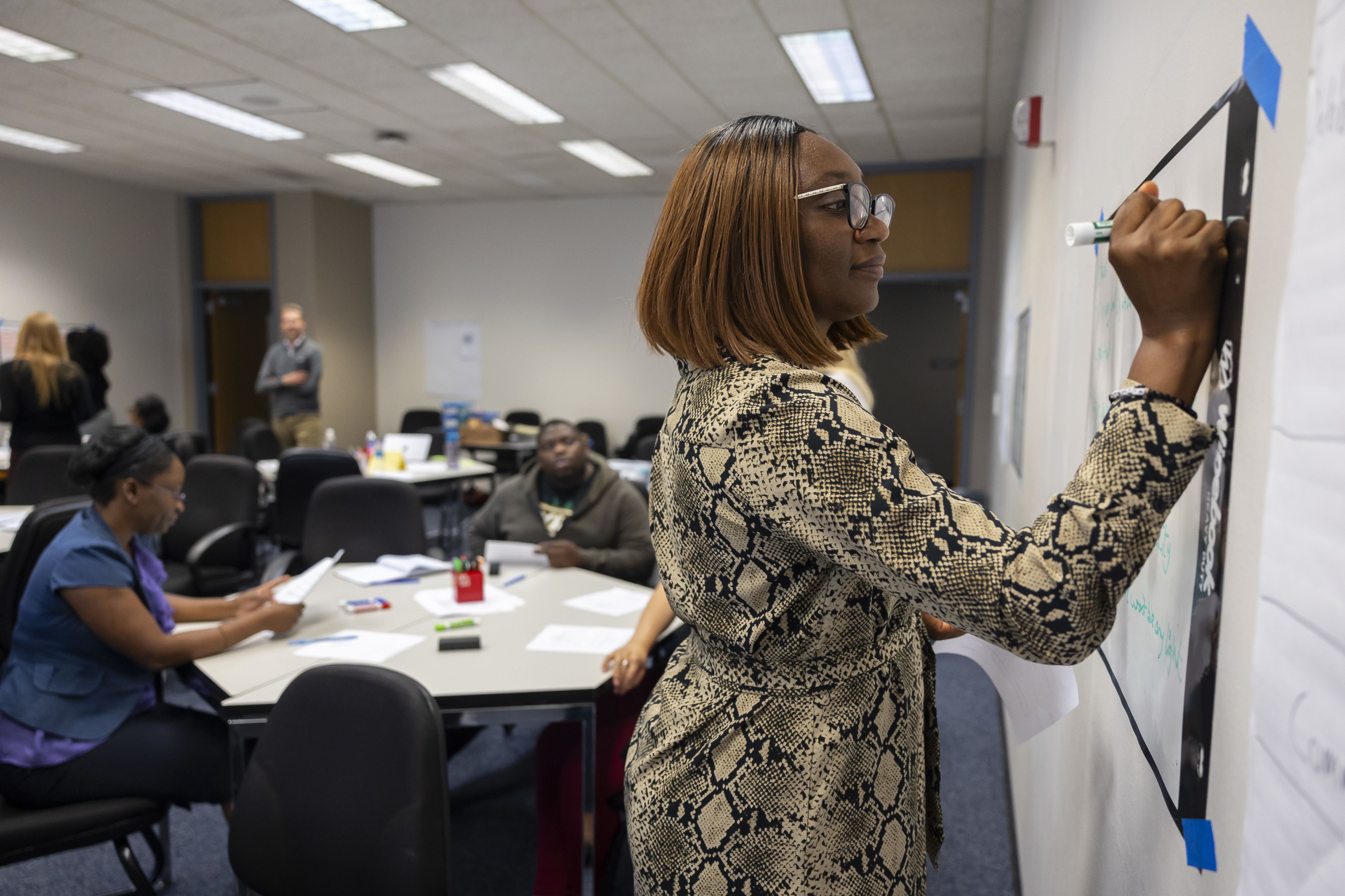

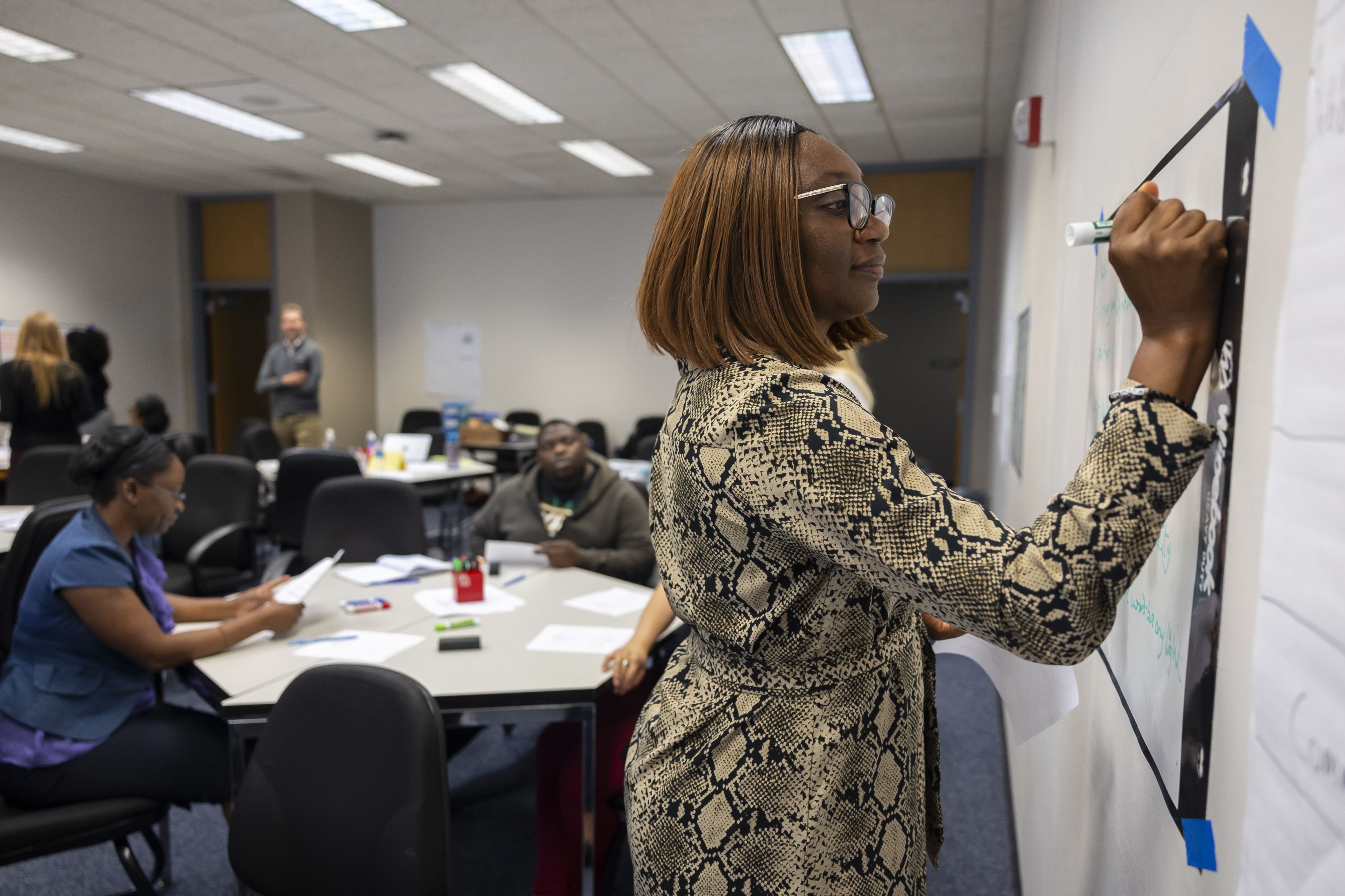

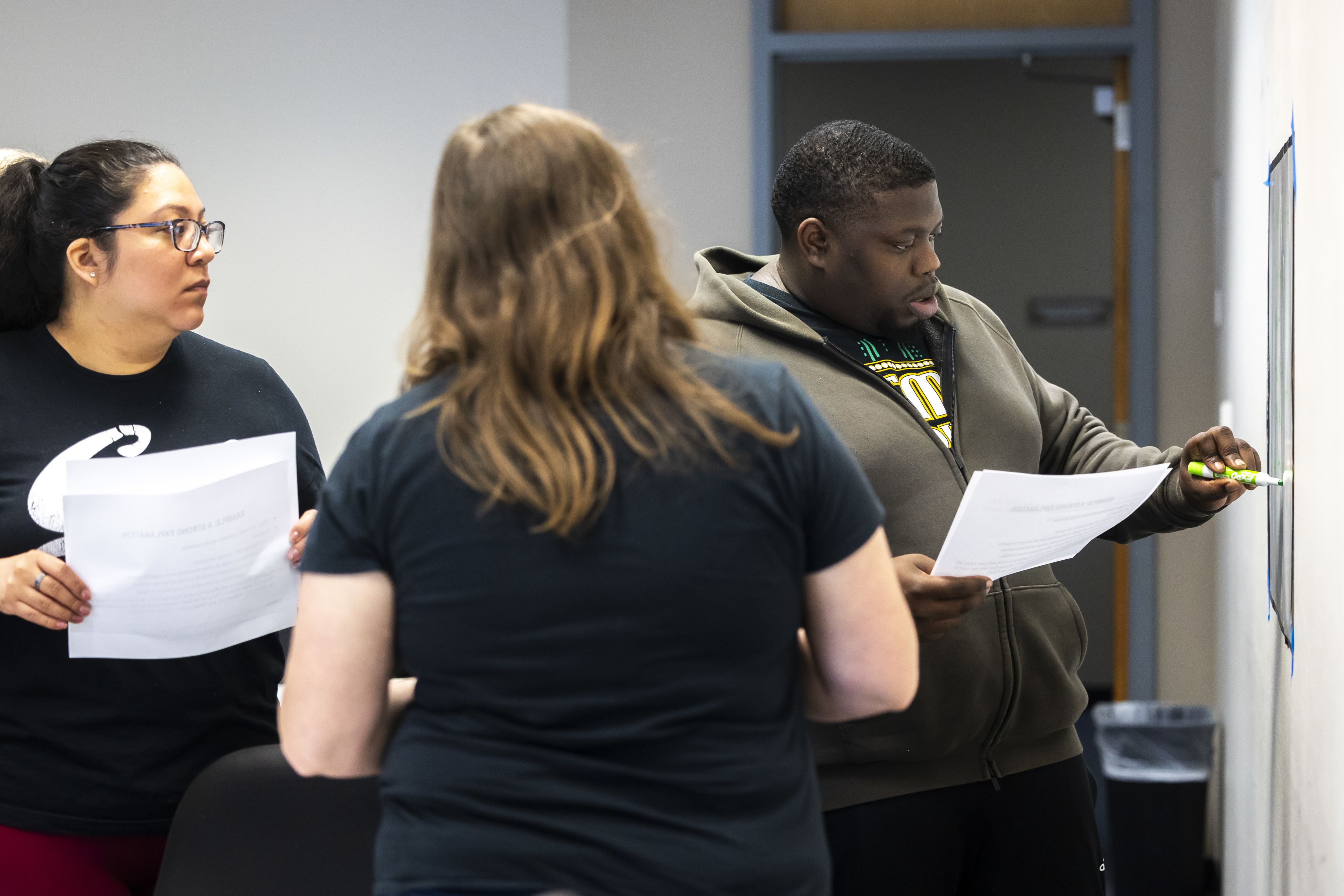

Future teacher Ejiro Ogbojo stood next to the whiteboard one day in late July, ready for his mission: guiding a group of students in a science lesson. How would a top predator — in this case, a hawk — be affected if the source of food for a creature at the bottom of the food web disappeared from the ecosystem?

He glanced at his notes and dove in. “When the seeds are removed, what do you think is going to happen?”

The loss of seeds will be bad news for sparrows, one of his “students” answered.

“Great observation,” Ogbojo responded and then reiterated a key point, like good teachers do. Sparrows eat seeds, and animals higher up the food chain eat sparrows.

It was great practice for his role as a middle school science teacher in Fort Bend County, and a key reason he switched to the UH program after starting an online alternative certification program . “Watching videos, reading material — I needed more interaction,” he said.

Ogbojo, 28, got plenty of that during the summer training session, as members of the College of Education’s teacher education faculty modeled strategies for leading classroom discussions and teaching complex concepts.

Earlier that morning Thompson had guided participants through an exercise often used in science classrooms — how does the size of a parachute affect the rate at which it descends? Students made their predictions before she shared the results. As most had guessed, the larger the parachute, the slower its descent.

Justin Burris, another professor, pointed out the effective teaching strategies he saw. Thompson listened as someone answered a question, then asked another group member to restate the original answer. That encourages everyone to listen, Burris said. “That was a great teacher move.”

And when she restated an answer, she followed up with, “Did I get what you said right?”

“What a powerful question,” Burris said. “A way to honor everyone’s thinking, to show that what you say matters in this class. That’s huge for kids.”

Ogbojo, who worked as a long-term substitute teacher after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in public health, absorbed those lessons. “Those are things I will be able to use to lead my classroom. I’m learning from actual teaching instructors, instead of just winging it.”

Future teacher Ejiro Ogbojo stood next to the whiteboard one day in late July, ready for his mission: guiding a group of students in a science lesson. How would a top predator — in this case, a hawk — be affected if the source of food for a creature at the bottom of the food web disappeared from the ecosystem?

He glanced at his notes and dove in. “When the seeds are removed, what do you think is going to happen?”

The loss of seeds will be bad news for sparrows, one of his “students” answered.

“Great observation,” Ogbojo responded and then reiterated a key point, like good teachers do. Sparrows eat seeds, and animals higher up the food chain eat sparrows.

It was great practice for his role as a middle school science teacher in Fort Bend County, and a key reason he switched to the UH program after starting an online alternative certification program. “Watching videos, reading material — I needed more interaction,” he said.

Ogbojo, 28, got plenty of that during the summer training session, as members of the College of Education’s teacher education faculty modeled strategies for leading classroom discussions and teaching complex concepts.

Earlier that morning Thompson had guided participants through an exercise often used in science classrooms — how does the size of a parachute affect the rate at which it descends? Students made their predictions before she shared the results. As most had guessed, the larger the parachute, the slower its descent.

Justin Burris, another professor, pointed out the effective teaching strategies he saw. Thompson listened as someone answered a question, then asked another group member to restate the original answer. That encourages everyone to listen, Burris said. “That was a great teacher move.”

And when she restated an answer, she followed up with, “Did I get what you said right?”

“What a powerful question,” Burris said. “A way to honor everyone’s thinking, to show that what you say matters in this class. That’s huge for kids.”

Ogbojo, who worked as a long-term substitute teacher after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in public health, absorbed those lessons. “Those are things I will be able to use to lead my classroom. I’m learning from actual teaching instructors, instead of just winging it.”

Bridging the Gap

Teacher candidates in the pilot program range from recent college graduates to mid-career professionals, and program officials expect the same mix will hold true for future cohorts as partnerships expand to additional school districts.

Anyone with a bachelor’s degree can apply, although aspiring math teachers are required to have taken 15 hours of college-level math classes. After completing the upfront training with UH, candidates will take a state content exam to demonstrate they have the knowledge required to teach their subject; they will complete the full certification process at the end of their first year teaching.

Horn, the College of Education dean and a scholar focused in part on teacher policy issues, said the traditional undergraduate teacher preparation program remains a core responsibility of the college.

“But if we take seriously our responsibility to support our region and our state, that is insufficient to address what is a true teacher shortage crisis,” she said. “We have to be part of a thoughtful solution that is moving us more quickly toward closing the gap between the need for highly qualified teachers and what currently exists.”

Paul Llacar

Paul Llacar

Data has shown that teachers who complete a traditional undergraduate teacher-prep program are more likely to say they felt ready for the classroom and less likely to quit after just a few years than those who earned certification through an online ACP. Ultimately, Horn said, strong preparation translates to better outcomes for students. “Everything we do in education ought to come back to benefit students and families. To do that, we have to have teachers who feel well prepared and well supported to do the work.”

Paul Llacar said the pilot program prepared him to finally pursue his passion to teach. He has worked in a variety of business fields since graduating with a bachelor’s degree in economics in 1997.

“They show us things we’re going to use in the classroom,” he said as he prepped to teach seventh grade math in Fort Bend ISD. “You’re learning what you need to know to be successful.”