Keeping an Eye on ALICE

University of Houston Is Major Remote Monitoring Site

for Experiment in CERN Large Hadron Collider

It’s one more curve ball thrown by the pandemic: In 2020, COVID-19 restrictions on global travel halted almost all international scientists’ visits to CERN, one of the world’s largest and most respected scientific research centers. That presented a formidable challenge at CERN, located on the border of Switzerland and France, but grew into opportunity for top research teams elsewhere, including the University of Houston.

"Our computers keep constant real-time watch on output from the CERN experiment happening more than 5,200 miles away."

CERN Globe of Science and Innovation (Courtesy: CERN)

CERN Globe of Science and Innovation (Courtesy: CERN)

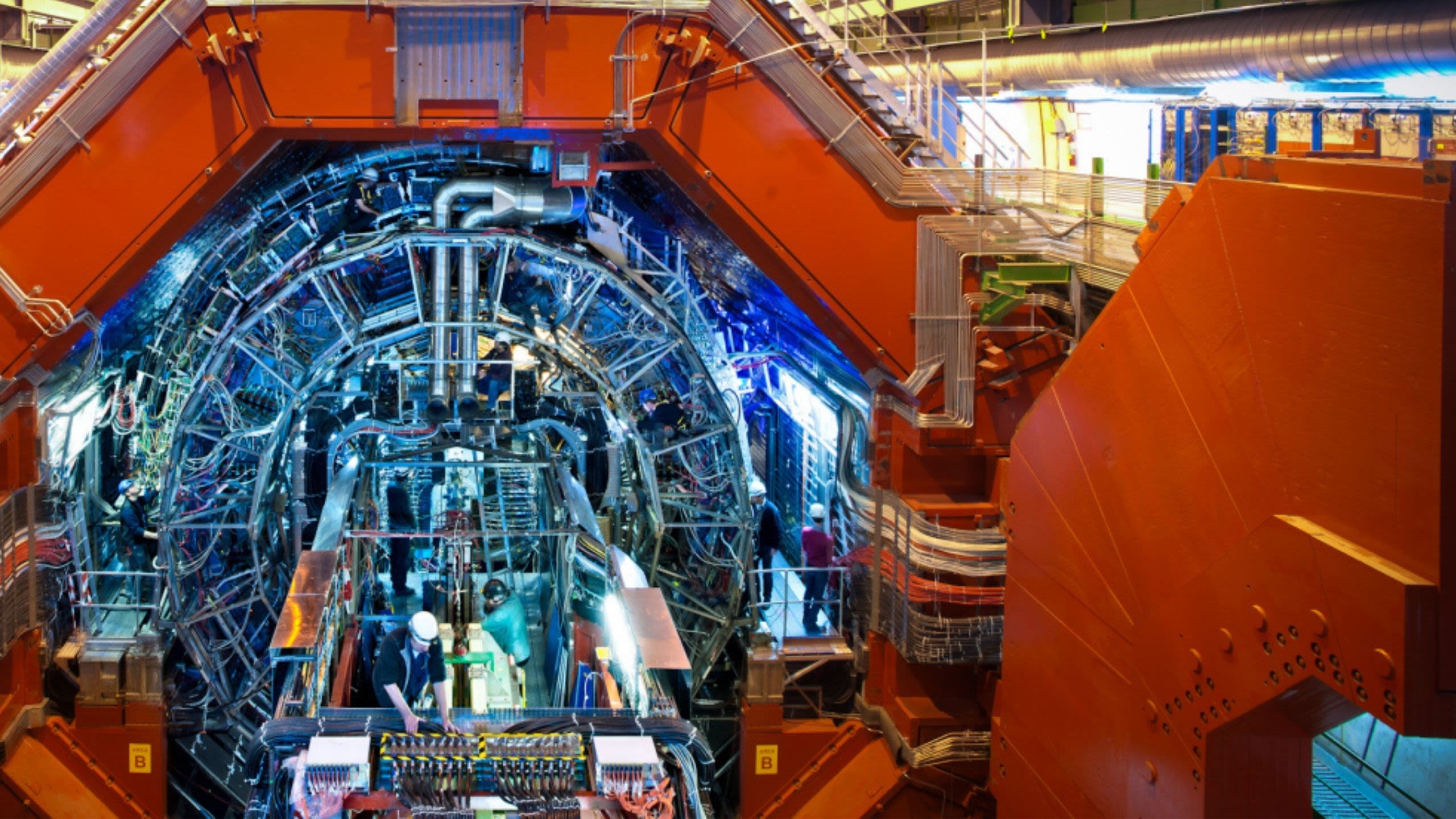

Despite the halt in the usual flow of visiting experts – among them, many of the world’s leading physicists, astrophysicists and data scientists – critical operations at CERN still demand constant monitoring. One of those operations is ALICE (A Large Ion Collider Experiment), which operates inside CERN’S Large Hadron Collider – the world’s largest and highest-energy particle collider.

The solution? As with so many situations these days, ALICE monitoring has gone remote, with stations established throughout Europe, Asia and at three U.S. locations – UH, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratories in California and University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Meanwhile at CERN, a small permanent crew of ALICE data specialists stays onsite.

“One of the most critical non-European monitoring sites for ALICE is here on the University of Houston campus. Our computers keep constant real-time watch on output from the CERN experiment happening more than 5,200 miles away. Our operations sometimes continue 24 hours a day throughout this year and maybe next,” said Anthony Timmins, associate professor of physics. “If there is any system glitch or interruption, we will know immediately and will alert the appropriate staff on location for the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.”

The ALICE collaboration seeks to add to scientists’ understanding of heavy-ion collisions. Physicists believe the quark-gluon plasma that results from such collisions is similar to what existed for a fraction of a second after the Big Bang.

ALICE monitoring made its official debut at UH on Sept. 1, when monitoring operations were transferred from a deep tunnel in the foothills of the Alps to a converted conference room in the UH Science & Research Building 1 of the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. After two months of preparation and training on equipment and software funded by a Department of Energy grant, the transition was smooth and operations since have flowed without a hiccup.

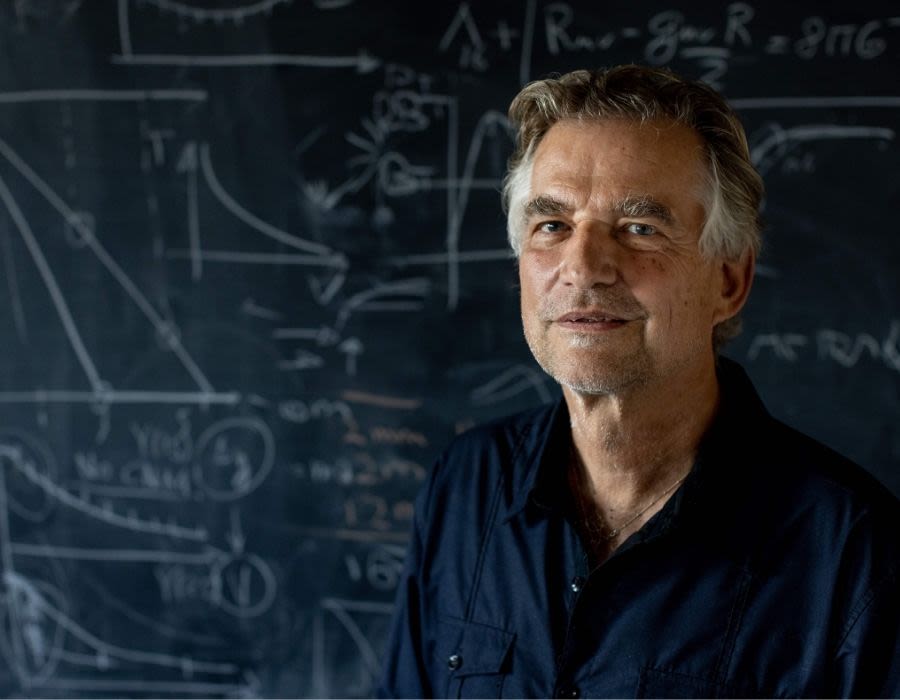

The UH monitoring team is directed by three physics faculty members – Timmins; Moores Professor of Physics Larry Pinsky; and M.D. Anderson Chair Professor of Physics Rene Bellwied, who is primary investigator of the project – and includes postdoctoral researchers Dhevan Gangadharan, Jihye Song and Christina Terrevoli; 10 doctoral students; and five undergraduates.

“From the global view, remote monitoring negates the need to travel to CERN and so reduces the carbon footprint. Here at home, it allows us to involve our undergraduates in high-level experiments and presents all our students and researchers with opportunities to learn from experts who will visit here to witness our ALICE monitoring system,” Timmins said.

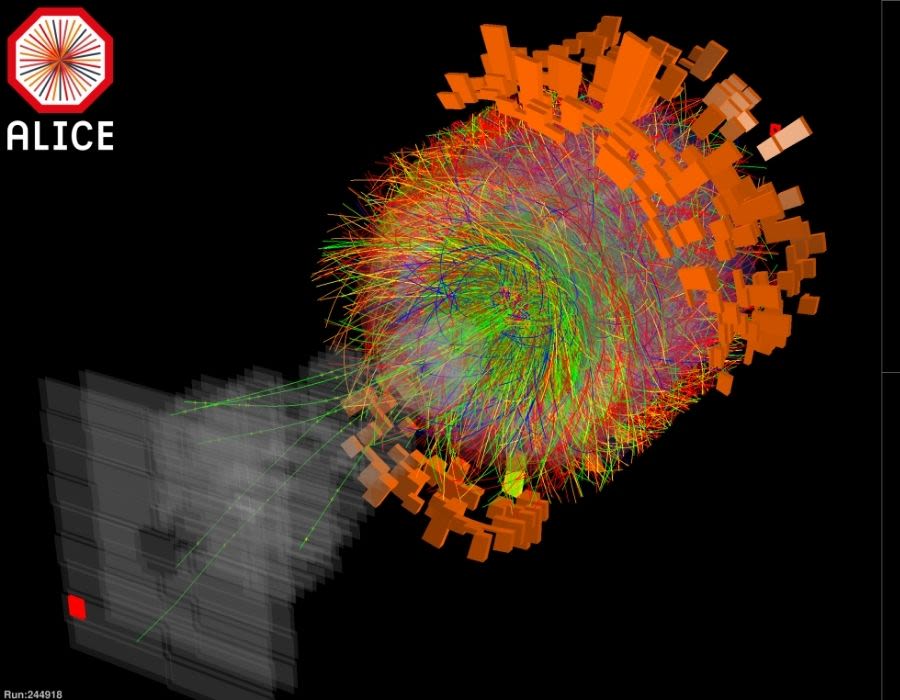

One of the first heavy-ion collisions with stable beams recorded by ALICE in 2015 (Courtesy: CERN).

One of the first heavy-ion collisions with stable beams recorded by ALICE in 2015 (Courtesy: CERN).

Doctoral student Alek Hutson monitors ALICE in Science & Research Building 1.

Doctoral student Alek Hutson monitors ALICE in Science & Research Building 1.

Rene Bellwied, MD Anderson Chair Professor of Physics, principal investigator of UH's ALICE monitoring station.

Rene Bellwied, MD Anderson Chair Professor of Physics, principal investigator of UH's ALICE monitoring station.

Anthony Timmins monitors ALICE with UH doctoral students.

Anthony Timmins monitors ALICE with UH doctoral students.

No longer term discussions about the remote-monitoring project are yet underway, but the UH team is hoping similar setups with CERN and other National Laboratories will continue long after pandemic restrictions ease.

CERN was founded in 1954 by 12 member countries. Current full membership consists of 23 member states, with Israel being the sole member outside Europe. The United States was granted observer status in 1997.

In 2019 (before pandemic restrictions), the CERN laboratory hosted 12,400 visiting professionals from institutions in more than 70 countries.

CERN headquarters is in Geneva, close to Switzerland’s border with France. Its Large Hadron Collider, the site of many current CERN activities, including ALICE, is located 328 feet underground, near the French village of Sergy.